Watch a video tutorial presented by AWS deep learning scientists and engineers at The Web Conference 2020.Read More

Alexa & Friends features Manoj Sindhwani, Alexa Speech vice president

Watch the recording of Manoj Sindhwani’s live interview with Alexa evangelist Jeff Blankenburg.Read More

Amazon scientists author popular deep-learning book

Dive into Deep Learning combines detailed instruction and math with hands-on examples and code.Read More

Learning to Segment Actions from Observation and Narration

We apply a generative segmental model of task structure, guided by narration, to action segmentation in video. We focus on unsupervised and weakly-supervised settings where no action labels are known during training. Despite its simplicity, our model performs competitively with previous work on a dataset of naturalistic instructional videos.Read More

Agile and Intelligent Locomotion via Deep Reinforcement Learning

Posted by Yuxiang Yang and Deepali Jain, AI Residents, Robotics at Google

Recent advancements in deep reinforcement learning (deep RL) has enabled legged robots to learn many agile skills through automated environment interactions. In the past few years, researchers have greatly improved sample efficiency by using off-policy data, imitating animal behaviors, or performing meta learning. However, sample efficiency remains a bottleneck for most deep reinforcement learning algorithms, especially in the legged locomotion domain. Moreover, most existing works focus on simple, low-level skills only, such as walking forward, backward and turning. In order to operate autonomously in the real world, robots still need to combine these skills to generate more advanced behaviors.

Today we present two projects that aim to address the above problems and help close the perception-actuation loop for legged robots. In “Data Efficient Reinforcement Learning for Legged Robots”, we present an efficient way to learn low level motion control policies. By fitting a dynamics model to the robot and planning for actions in real time, the robot learns multiple locomotion skills using less than 5 minutes of data. Going beyond simple behaviors, we explore automatic path navigation in “Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning for Quadruped Locomotion”. With a policy architecture designed for end-to-end training, the robot learns to combine a high-level planning policy with a low-level motion controller, in order to navigate autonomously through a curved path.

Data Efficient Reinforcement Learning for Legged Robots

A major roadblock in RL is the lack of sample efficiency. Even with a state-of-the-art sample-efficient learning algorithm like Soft Actor-Critic (SAC), it would still require more than an hour of data to learn a reasonable walking policy, which is difficult to collect in the real world.

In a continued effort to learn walking skills using minimal interaction with the real-world environment, we present another, more sample-efficient model-based method for learning basic walking skills that dramatically reduces the training data needed. Instead of directly learning a policy that maps from environment state to robot action, we learn a dynamics model of the robot that estimates future states given its current state and action. Since the entire learning process requires less than 5 minutes of data, it could be performed directly on the real robot.

We start by executing random actions on the robot, and fit the model to the data collected. With the model fitted, we control the robot using a model predictive control (MPC) planner. We iterate between collecting more data with MPC and re-training the model to better fit the dynamics of the environment.

|

| Overview of the model-based learning pipeline. The system alternates between fitting the dynamics model and collecting trajectories using model predictive control (MPC). |

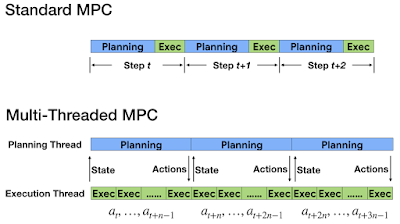

In standard MPC, the controller plans for a sequence of actions at each timestep, and only executes the first of the planned actions. While online replanning with regular feedback from the robot to the controller makes the controller robust to model inaccuracies, it also poses a challenge for the action planner, as planning must finish before the next step of the control loop (usually less than 10ms for legged robots). To satisfy such a tight time constraint, we introduce a multi-threaded, asynchronous version of MPC, with action planning and execution happening on different threads. As the execution thread applies actions at a high frequency, the planning thread optimizes for actions in the background without interruption. Furthermore, since action planning can take multiple timesteps, the robot state would have changed by the time planning has finished. To address the problem with planning latency, we devise a novel technique to compensate, which first predicts the future state when the planner is expected to finish its computation, and then uses this future state to seed the planning algorithm.

|

| We separate action planning and execution on different threads. |

Although MPC refreshes the action plan frequently, the planner still needs to work over long action horizons to keep track of the long-term goal and avoid myopic behaviors. To that end, we use a multi-step loss function, a reformulation of the model loss function that helps to reduce error accumulation over time by predicting the loss over a range of future steps.

Safety is another concern for learning on the real robot. For legged robots, a small mistake, such as missing a foot step, could lead to catastrophic failures, from the robot falling to the motor overheating. To ensure safe exploration, we embed a stable, in-place stepping gait prior, that is modulated by a trajectory generator. With the stable walking prior, MPC can then safely explore the action space.

Combining an accurate dynamics model with an online, asynchronous MPC controller, the robot successfully learned to walk using only 4.5 minutes of data (36 episodes). The learned dynamics model is also generalizable: by simply changing the reward function of MPC, the controller is able to optimize for different behaviors, such as walking backwards, or turning, without re-training. As an extension, we use a similar framework to enable even more agile behaviors. For example, in simulation the robot learns to backflip and walk on its rear legs, though these behaviors are yet to be learned by the real robot.

|

| The robot learns to walk using only 4.5 minutes of data. |

|

| The robot learns to backflip and walk with rear legs using the same framework. |

Combining low-level controller with high-level planning

Although model-based RL has allowed the robot to learn simple locomotion skills efficiently, such skills are insufficient for handling complex, real-world tasks. For example, in order to navigate through an office space, the robot may have to adjust its speed, direction and height multiple times, instead of following a pre-defined speed profile. Traditionally, people solve such complex tasks by breaking them down into multiple hierarchical sub-problems, such as a high-level trajectory planner and a low-level trajectory-following controller. However, manually defining a suitable hierarchy is typically a tedious task, as it requires careful engineering for each sub-problem.

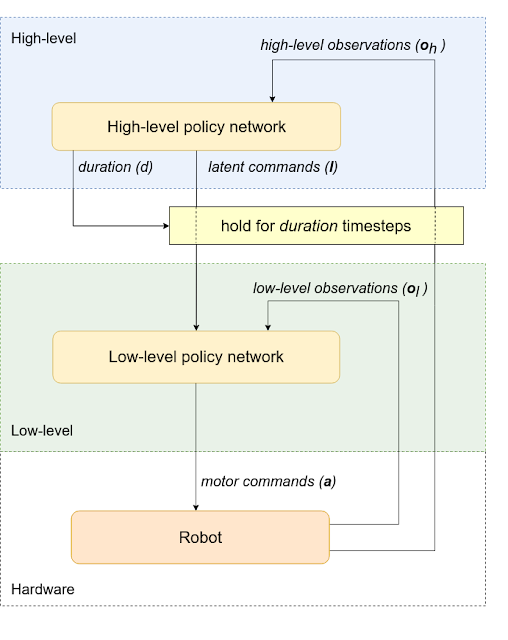

In our second paper, we introduce a hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL) framework that can be trained to automatically decompose complex reinforcement learning tasks. We break down our policy structure into a high-level and a low-level policy. Instead of designing each policy manually, we only define a simple communication protocol between the policy levels. In this framework, the high-level policy (e.g., a trajectory planner) commands the low-level policy (such as the motion control policy) through a latent command, and decides for how long to hold that command constant before issuing a new one. The low-level policy then interprets the latent command from the high-level policy, and gives motor commands to the robot.

To facilitate learning, we also split the observation space into high-level (e.g., robot position and orientation) and low-level (IMU, motor positions) observations, which are fed to their corresponding policies. This architecture naturally allows the high-level policy to operate at a slower timescale than the low-level policy, which saves computation resources and reduces training complexity.

Since the high-level and low-level policies operate at discrete timescales, the entire policy structure is not end-to-end differentiable, and standard gradient-based RL algorithms like PPO and SAC cannot be used. Instead, we choose to train the hierarchical policy through augmented random search (ARS), a simple evolutionary optimization method that has demonstrated good performance in reinforcement learning tasks. Weights of both levels of the policy are trained together, where the objective is to maximize the total reward from the robot trajectory.

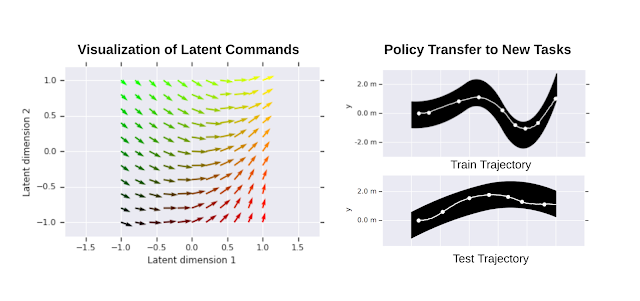

We test our framework on a path-following task using the same quadruped robot. In addition to straight walking, the robot needs to steer in different directions to complete the task. Note that as the low-level policy does not know the robot’s position in the path, it does not have sufficient information to complete the entire task on its own. However, with the coordination between the high-level and low-level policies, steering behavior emerges automatically in the latent command space, which allows the robot to efficiently complete the path. After successful training in a simulated environment, we validate our results on hardware by transferring an HRL policy to a real robot and recording the resulting trajectories.

To further demonstrate the learned hierarchical policy, we visualized the behavior of the learned low-level policy under different latent commands. As shown in the plot below, different latent commands can cause the robot to walk straight, or turn left or right at different rates. We also test the generalizability of low-level policies by transferring them to new tasks from a similar domain, which, in our case, includes following a path with different shapes. By fixing the low-level policy weights and only training the high-level policy, the robot could successfully traverse through different paths.

Conclusion

Reinforcement learning poses a promising future for robotics by automating the controller design process. With model-based RL, we enabled efficient learning of generalizable locomotion behaviors directly on the real robot. With hierarchical RL, the robot learned to coordinate policies at different levels to achieve more complex tasks. In the future, we plan to bring perception into the loop, so that robots can operate truly autonomously in the real world.

Acknowledgements

Both Deepali Jain and Yuxiang Yang are residents in the AI Residency program, mentored by Ken Caluwaerts and Atil Iscen. We would also like to thank Jie Tan and Vikas Sindhwani for support of the research, and Noah Broestl for managing the New York AI Residency Program.

Visualizing the world beyond the frame

Most firetrucks come in red, but it’s not hard to picture one in blue. Computers aren’t nearly as creative.

Their understanding of the world is colored, often literally, by the data they’ve trained on. If all they’ve ever seen are pictures of red fire trucks, they have trouble drawing anything else.

To give computer vision models a fuller, more imaginative view of the world, researchers have tried feeding them more varied images. Some have tried shooting objects from odd angles, and in unusual positions, to better convey their real-world complexity. Others have asked the models to generate pictures of their own, using a form of artificial intelligence called GANs, or generative adversarial networks. In both cases, the aim is to fill in the gaps of image datasets to better reflect the three-dimensional world and make face- and object-recognition models less biased.

In a new study at the International Conference on Learning Representations, MIT researchers propose a kind of creativity test to see how far GANs can go in riffing on a given image. They “steer” the model into the subject of the photo and ask it to draw objects and animals close up, in bright light, rotated in space, or in different colors.

The model’s creations vary in subtle, sometimes surprising ways. And those variations, it turns out, closely track how creative human photographers were in framing the scenes in front of their lens. Those biases are baked into the underlying dataset, and the steering method proposed in the study is meant to make those limitations visible.

“Latent space is where the DNA of an image lies,” says study co-author Ali Jahanian, a research scientist at MIT. “We show that you can steer into this abstract space and control what properties you want the GAN to express — up to a point. We find that a GAN’s creativity is limited by the diversity of images it learns from.” Jahanian is joined on the study by co-author Lucy Chai, a PhD student at MIT, and senior author Phillip Isola, the Bonnie and Marty (1964) Tenenbaum CD Assistant Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

The researchers applied their method to GANs that had already been trained on ImageNet’s 14 million photos. They then measured how far the models could go in transforming different classes of animals, objects, and scenes. The level of artistic risk-taking, they found, varied widely by the type of subject the GAN was trying to manipulate.

For example, a rising hot air balloon generated more striking poses than, say, a rotated pizza. The same was true for zooming out on a Persian cat rather than a robin, with the cat melting into a pile of fur the farther it recedes from the viewer while the bird stays virtually unchanged. The model happily turned a car blue, and a jellyfish red, they found, but it refused to draw a goldfinch or firetruck in anything but their standard-issue colors.

The GANs also seemed astonishingly attuned to some landscapes. When the researchers bumped up the brightness on a set of mountain photos, the model whimsically added fiery eruptions to the volcano, but not a geologically older, dormant relative in the Alps. It’s as if the GANs picked up on the lighting changes as day slips into night, but seemed to understand that only volcanos grow brighter at night.

The study is a reminder of just how deeply the outputs of deep learning models hinge on their data inputs, researchers say. GANs have caught the attention of intelligence researchers for their ability to extrapolate from data, and visualize the world in new and inventive ways.

They can take a headshot and transform it into a Renaissance-style portrait or favorite celebrity. But though GANs are capable of learning surprising details on their own, like how to divide a landscape into clouds and trees, or generate images that stick in people’s minds, they are still mostly slaves to data. Their creations reflect the biases of thousands of photographers, both in what they’ve chosen to shoot and how they framed their subject.

“What I like about this work is it’s poking at representations the GAN has learned, and pushing it to reveal why it made those decisions,” says Jaakko Lehtinen, a professor at Finland’s Aaalto University and a research scientist at NVIDIA who was not involved in the study. “GANs are incredible, and can learn all kinds of things about the physical world, but they still can’t represent images in physically meaningful ways, as humans can.”

Enhanced POET: Open-Ended Reinforcement Learning through Unbounded Invention of Learning Challenges and their Solutions

Jeff Clune and Kenneth Stanley were co-senior authors on this work and our associated research paper.

Machine learning (ML) powers many technologies and services that underpin Uber’s platforms, and we invest in advancing fundamental ML research and engaging with …

The post Enhanced POET: Open-Ended Reinforcement Learning through Unbounded Invention of Learning Challenges and their Solutions appeared first on Uber Engineering Blog.

How Alexa knows when you’re talking to her

Leveraging semantic content improves performance of acoustic-only model for detecting device-directed speech.Read More

Leveraging Compositionality for One-Shot Imitation Learning

How do you teach a robot to pack your groceries into different boxes? While modern industrial robots are incredibly capable and precise, they require tremendous expertise to program and are designed to execute the exact same motion millions of times. Trying to program a robot to be able to pick up any kind of groceries, each with different characteristics, geometries, and weight, and pack them in the right boxes, would be incredibly difficult.

In this post, we introduce methods for teaching a robot to learn new tasks by showing a single demonstration of the task. This is also called one-shot imitation learning. To get a better idea of why this is an important problem, let’s first imagine a scenario where a robot is responsible for packaging in the warehouse: It needs to pick up all kinds of items people order from storage and then place the objects in shipping containers. The size of the problem can quickly become intractable if we consider the combination of different objects and different containers. For example, packaging five types of items into five types of shipping containers results in 120 possible combinations. This means that the robot would need to learn 120 different policies to accomplish all the different combinations. Imagine if you had to give instructions to someone to pack your groceries. That seems easy–millions of humans do this every day. But here’s a twist: this robot has never seen a milk carton or a paper bag. And the robot also doesn’t know how to use its arm, so you need to instruct it where to place its hand (close to the milk carton), when to close its hand (when it’s on top of the jug), and how to move the milk to the right paper bag. Now imagine if for every single item and every single bag you needed to give these detailed instructions for this robot. That is how difficult it is to program a robot to do a task that is simple for humans.

But from another perspective, we do know that packaging five types of items into five types of shipping containers is not so complicated; ultimately, it just involves picking up a sequence of objects and putting them into a box. And, we know that picking up and placing different items into the same shipping container is basically the same thing regardless of the item. In other words, we can use the same skill to place different objects into the same container, and consider this a subtask of the full job to be done. We can take this idea further: even picking up different objects is quite similar since moving toward objects is independent of the object type. Based on this insight, we would not have to really write hundreds of entirely different programs to package five items into five containers. Instead, we can focus on implementing primitive skills like grasping, moving, dropping, which can be composed to package items in arbitrary containers.

In this post, we discuss approaches that aim to leverage the above intuition of compositionality, i.e., generalizing to new tasks by composing pieces of smaller tasks, to reduce the effort robots need to learn new tasks. We refer to structured representations that allow simpler constituents to recombine and form new representations as “compositional priors”. In each section, we gradually build stronger compositional priors into our models and observe its effect on learning efficiency for robotics tasks such as the one above.

We will first define the problem setup and what we mean for robots to learn new tasks, which provides a unified setup for us to evaluate and compare different approaches. Then, we shall discuss the following approaches: (i) Neural Task Programming, (ii) Neural Task Graph Networks, (iii) Continuous Planner. We hope that these more human efforts can translate to more efficient learning of our robots.

The Problem: One-shot Imitation Learning

We mentioned that we hope to leverage compositional prior to improve learning efficiency of robots. It is therefore important that we use a unified setup to compare different approaches. However, there are many ways a robot can learn. It can directly interact with the environment and use trial-and-error to learn actions that can lead to “good” consequences. On the other hand, the robot can also learn new tasks by following demonstrations: an expert, or someone who knows how the task is done, can demonstrate (potentially many times) to the robot how to complete the task. In this post we consider the latter, and constrain the robot to learn from a single demonstration, which is known as one-shot imitation learning.

Humans can learn many things from a single demonstration. For example, if someone wants to learn how to package different items into shipping containers, then all we need is a single demonstration to specify what items should go into what containers. While it seems natural for humans, how can we have agents or robots do the same? One clever approach is to formulate it as another learning problem: we can have the agent ‘learn to learn’, so that it is trained to be able to learn a new task from a single demonstration.

It is important to differentiate the two types of “learning” here. The first type is a more ordinary one: the learning for an agent to do new tasks like packaging items in a warehouse, i.e. one-shot imitation learning. For this type of learning, the agent always only has a single demonstration without further interaction with the environment in our setting. But remember, the agent does not know how to do this at the outset. So, the second type of learning refers to the agent becoming able to do the first type of learning, i.e. learning how to be able to do a task from a single demonstration well. When we say we would like to improve the “learning efficiency” of our robots or agents, we mean to improve the learning efficiency of this second type of learning: how can we have agents that quickly learn the ability to do new tasks from a single demonstration. We want to improve efficiency of this because providing demonstrations to robotics is fairly time consuming, and if it is necessary to provide millions of such demonstrations for the agent to learn one-shot imitation

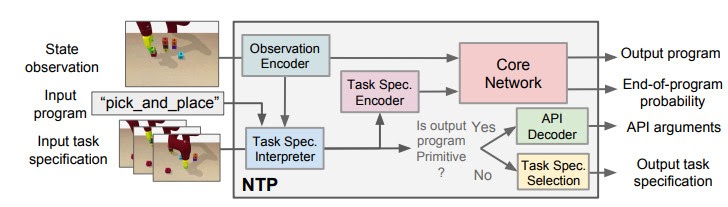

Approach 1: Neural Task Programming (NTP)

As we have discussed, we have the intuition that an overall objective (e.g., packaging items) can be decomposed into simpler objectives (e.g., picking certain items) recursively (i.e. subtasks can also be composed of subtasks). This allows us to write robot programs more efficiently since we get to reuse a lot of the smaller pieces for making these programs, and we hope we can apply the same intuition to our one-shot imitation agent so that it can learn to learn new tasks more efficiently.

One may notice that this intuition emulates a typical computer program, 1) invoking a sub-program 2) return to the calling program (return). This is the essence of neural program synthesis, which uses neural networks to simulate computer programs. Neural program synthesis has many advantages over ordinary neural networks, such as learning discrete operations. More details about the model architecture and the idea of neural program synthesis can be found in our paper, its predecessor NPI 1 (Neural Programmer-Interpreter), and seminal works such as Neural Turing Machine 2.

Similarly to the Neural Programmer-Interpreter, Neural Task Programming (NTP) achieves this program-like recursive decomposition by supervised training. Given the current task, we provided the model with the correct decomposition of that task into subtasks, and trained the model to perform this decomposition based on the current state observation and task specification (or demonstration).

In the figure we use the “pick_and_place” as the input program or objective, which we aim to decompose. The module is trained to have four outputs:

- The task decomposition; in this case we know “pick_and_place” can be further decomposed to “pick.”

- The end-of-program probability or whether to “return” the current program. For example, we can decompose a “pick_and_place” into a “pick” and a “place,” and the “pick_and_place” is complete or can return only if both the “pick” and the “place” are done.

- “Task Specification” when invoking a sub-program and continuing with the recursion, in which case we just update the scope of the task specification for the next recursion.

- “API Arguments” when invoking a sub-program and we reach the bottom of recursion, in which case we call the robot to execute actual movements and provide the API arguments such as object should the robot arm move to. 2)

This last type of output, which leads to a hierarchical decomposition of task specification/demonstration, is another key factor of NTP. Take “pick_and_place” again as an example. There might be multiple instances of “pick_and_place”s in the full task specification: we pick up different objects and place them onto/into different objects. How does the model know what objects we are currently interested in for this specific “pick_and_place”? The obvious answer is that we should compare the current state observation with the task specification, by which we can figure out the current progress (i.e., what “pick_and_place”s are done) and decide what objects to pick and place. This can be challenging if the task specification is long.

On the other hand, it is more ideal if the NTP program to process “pick_and_place” only sees the part of the specification that is relevant to this specific “pick_and_place”. In this case, we only have to recognize the objects in the clipped specification instead of searching from the full specification. In fact, this clipped specification is all we need to correctly decompose this “pick_and_place.” Therefore, we recursively decompose and update the scope of task specifications as outputs of NTP modules. A long task demonstration thus can be decomposed recursively to shorter clips as the program traverses down the hierarchy. In more technical terms, the hierarchical decomposition of demonstrations prevents the model from learning spurious dependencies on training data, resulting in better reusability of each program. Below is an example showing how NTP hierarchically decomposes a complex long-horizon task.

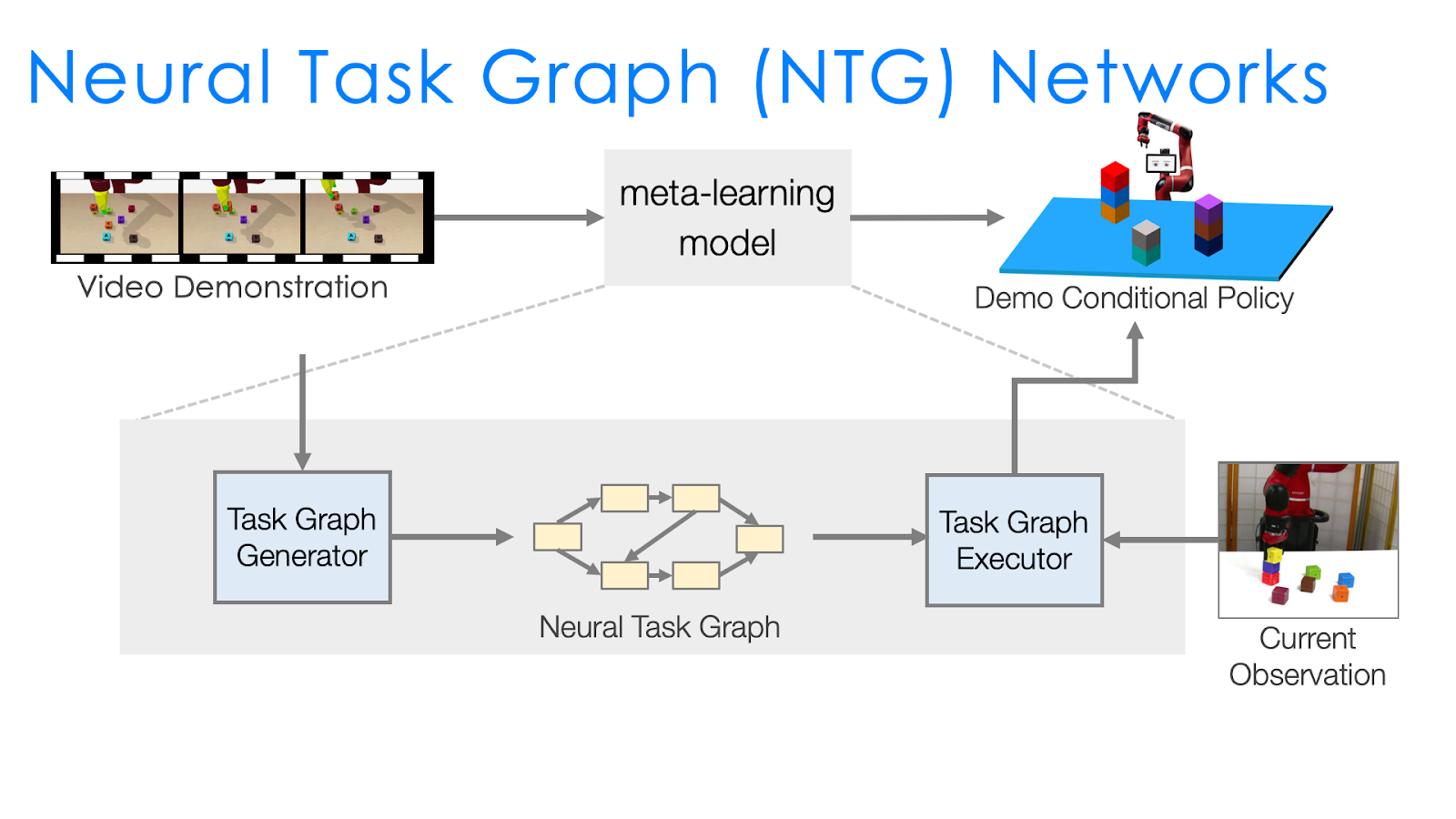

Approach 2: Neural Task Graph Networks (NTG)

Recall that the “learning efficiency” we are interested in is how fast we can train a model so that the model can learn new tasks with a single demonstration. We have introduced NTP, which learns to hierarchically decompose tasks for execution. Our intuition is that it is easier to learn to decompose tasks compared to directly determining what the robot action should be based on an arbitrary task demonstration that can be quite long. In other words, if models can more efficiently learn to decompose tasks, then we can improve our robot’s learning efficiency But the NTP module still has to learn a lot of very complicated tasks all at the same time: what programs to decompose, whether the current program is finished, what are the arguments for the subprograms, how to change the scope of task specification. In addition, a single error at the higher level can propagate and affect all the following decompositions. For example, if the task specification scope for “pick_and_place” is off, then we cannot have the correct scopes for “pick” and “place.”

Therefore, the next approach, Neural Task Graph Networks (NTG) improves over NTP by changing two things to make learning easier. First, we introduce several modules to specialize in different aspects instead of having a single NTP module to learn everything. This modularization more explicitly specifies what each module should learn. Second, task decomposition is explicitly represented with a task graph, which captures all the possible ways to complete a task. This is in contrast to NTP, which trains the agent to decompose tasks but still allows it to not do so, and leaves it up to the agent to have a black box mechanism for doing the decomposition. With the use of the task graph, task execution is explicitly represented by a traversal of the graph, and so unlike with NTP similar tasks with similar task graphs would be guaranteed to have very similar execution traces.

Specifically, the two key components of NTG are:

- A task graph generator that parses the dependencies between sub-programs for this task and uses it as the task graph.

- A task graph executor that picks the node or sub-program to execute based on the structure of the task graph.

The variations between tasks are roughly captured by the task graph and handled by the task graph generator. Therefore, what needs to be done by the task graph executor is much easier than an NTP module. The task graph executor only needs to decide the action conditioned on the task graph, which already explicitly represents the task structure. We can think of task graph generation as a supervised learning problem that we expect to generalize better between tasks compared to NTP , since we reduce the difficulty of what NTG has to learn compared to NTP by introducing the task graph as an intermediate representation.

There is still a lot that needs to be done by the executor. For example, to serve as a policy, it needs to understand the task progress based on the current observation. It also needs to decide the action based on both the task progress and the task graph. Instead of having a single network to do all, we design two modules, node localizer and edge classifier, and specify how they should work together to serve as a policy depending on both the task progress and the task graph.

As shown in the above animation, given the observation we first use node localizer to localize ourselves in the graph. This is equivalent to recognizing what actions have just finished and measuring the progress of the task. Based on the current node, the structure of the task graph constraints the possible next actions (nodes connected by outgoing edges). We then train a classifier to decide which outgoing edge to take. And this is equivalent to selecting the action. This structural approach significantly improves the generalization of NTG.

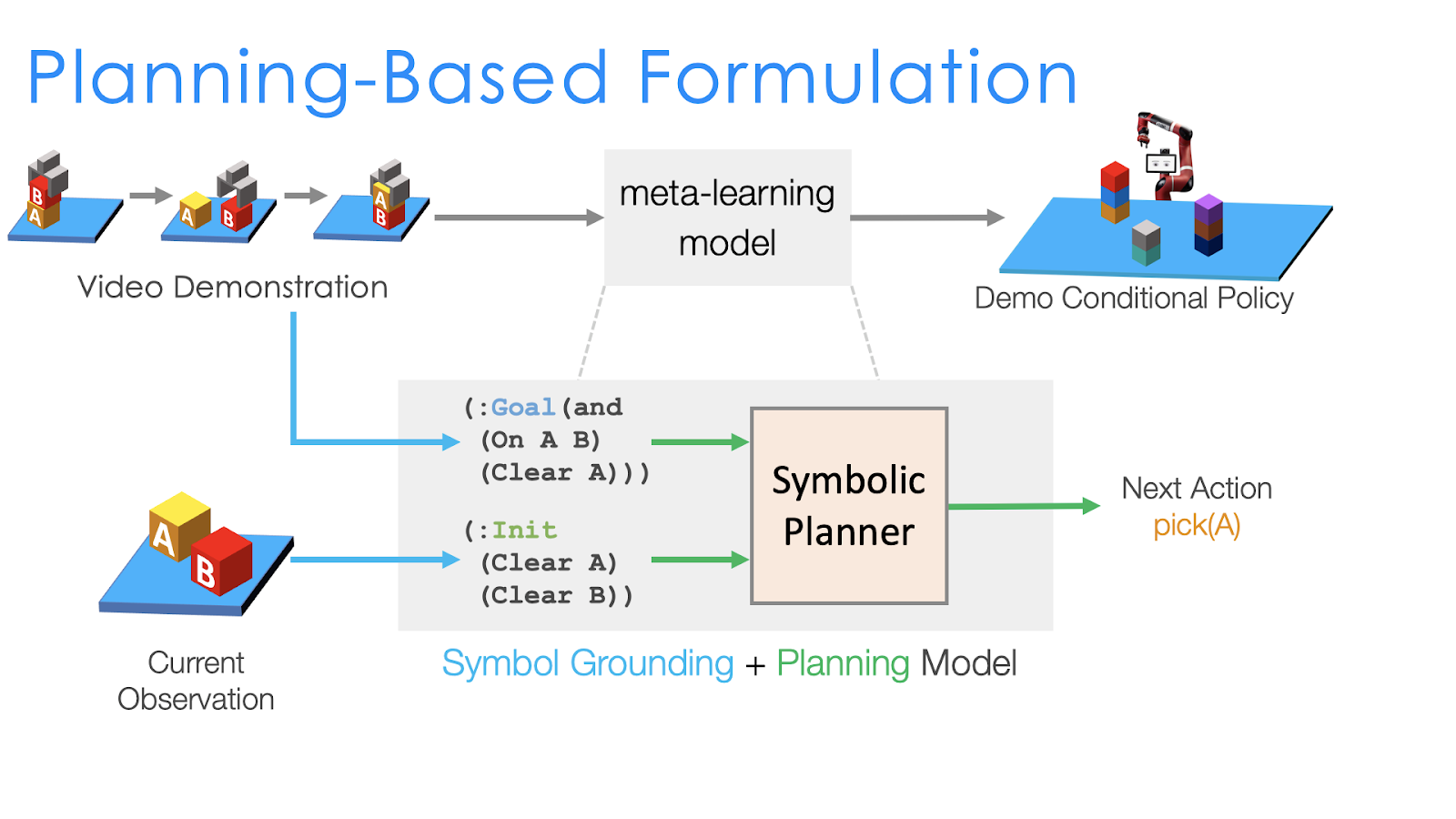

Approach 3: Planning-Based Formulation for One-Shot Imitation Learning

We have discussed how we can incorporate compositional prior into our model so that it can learn to learn new tasks more efficiently. This can be done by training the model to perform hierarchical decomposition (NTP) or incorporate compositional structure like a task graph (NTG). Both of the approaches need supervised data for training, which could be hard to annotate at scale. This limits the practicality of these approaches.

We address this challenge by observing that there are general rules about task execution we can easily write down, instead of just providing individual examples of task decomposition. Let us go back to our initial example of packaging five types of items into five types of shipping containers. To pick-up an item, the robot arm needs to be empty. Or to place the item in a container, the robot needs to already be holding the item, and the container needs to be empty. We can also write down general decomposition rules: “pick_and_place” should always be decomposed as “pick” and “place.” These are things we as humans can quickly write down, and are applicable to all 120 tasks, and even potentially other combinations beyond the fixed number of objects and containers. This is the idea of planning domain definition. We write down general rules in a domain (the domain of packaging items in this case), and these rules will constrain what our robot can do for the whole domain that is applicable to all the tasks.

The next question is how can we leverage the above definitions written down by humans? In some sense, NTP incorporates the compositional prior implicitly through supervised training, while NTG does it explicitly with the task graph. Here, these domain definitions allow us to enforce an even stronger compositional prior since we are given the rules and constraints of how tasks should generally be decomposed and therefore do not need to train a model to mimic the decomposition. All we need is to search for a sequence of actions that follows the predefined decomposition.

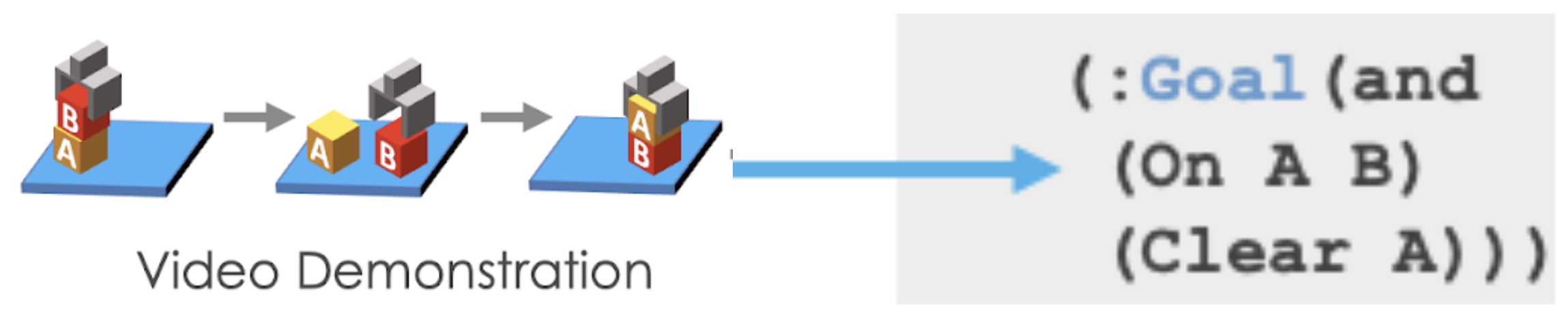

How do we do that? Given the full domain definition, which specifies what an agent can do at certain situations, a symbolic planner (a known algorithm which does not need to be learned) can search for a sequence of actions to achieve a certain goal. For example, if the goal is to put an item into a container, then the planner can automatically output the sequence of actions (1) put-down whatever is in the hand, (2) pick-up the item, (3) move to the container, (3) release the item into the container. If we have a planner, then it can significantly reduce the complexity of one-shot imitation learning. We just have to parse the goal of the task from the demonstration, and the planner can automatically decide what sequence of actions our robot needs to do. This leads to our planning-based formulation for one-shot imitation learning.

Since we can now have the planner as a given, instead of outputting the full task graph from the single demonstration like in NTG, in the planning based formulation we only need to learn to infer the symbolic goal of the task. For example, in the above figure, we have two blocks A and B with the goal being to stack A onto B. So to decide on which motions the robot needs to execute, the planning based formulation performs the following two steps:

Obtain the symbolic representation of the current state And of the goal state.

Feed both the current and goal state into the symbolic planner, which can automatically search for the sequence of actions that will transform the initial (current) state to the goal state and complete the task.

In contrast to NTG, where the transitions between nodes are learned and generated from the demonstration, here the possible transitions between states are already specified in the domain definition (e.g., the agent can only pick-up objects if the hand is empty). This further decoupled the execution from the generalization, which makes the learning of our model even easier at the cost of further human effort to define the domain. However, as shown in the examples, we are defining general rules that are applicable to all the tasks and do not need to scale the effort with the amount of data we use.

One thing that is still missing is how do we get the symbolic goal and initial states from the demonstration and the observation. This is also called the symbol grounding problem. As it can be formulated as a learning problem, we again use supervised learning to train neural networks to do this. One problem with symbol grounding is that it can be brittle (perception needs to be perfect even when there is uncertainty) , and so we also developed a continuous planner to directly work on the outputs of our symbol grounding neural networks. We will not further discuss this approach in this blogpost , but you can check out the paper at the end if you are interested!

One-Shot Imitation Learning Evaluation

Now we have discussed three approaches that incorporate compositional prior in their designs, with gradually more human efforts and harder constraints. How does each affect the efficiency for models to learn to learn new tasks?

Recall that we are interested in the one-shot imitation learning setting, where we want the models to learn new tasks based on a single demonstration. For packaging 5 types of items into 5 containers, we would like to just show a demonstration of how we want the items being packaged instead of programming more than a hundred distinct policies. In this example, the domain is packaging items, and each unique packaging combination of items and containers is a distinct task. For our evaluation, we use the Block Stacking domain, where each block configuration is defined as a distinct task. We use Block Stacking instead of item packaging because there can be much more block configurations, and thus much more distinct tasks in the Block Stacking domain. The large number of possible tasks is important for us to compare different approaches.

Based on this setting, we train our models with successful demonstrations generated by our block stacking simulator. At testing/evaluation, we show a demonstration of a new task or block configuration that is not included in the demonstrations for training, and we evaluate if the model can successfully stack the blocks into the same configuration based on this single demonstration. While the models are trained with the same demonstrations generated by our simulator, the trained model can be instantiated on a robot for high-level action decision. For example, we will show NTP’s results on a 7-DoF Sawyer arm using position control.

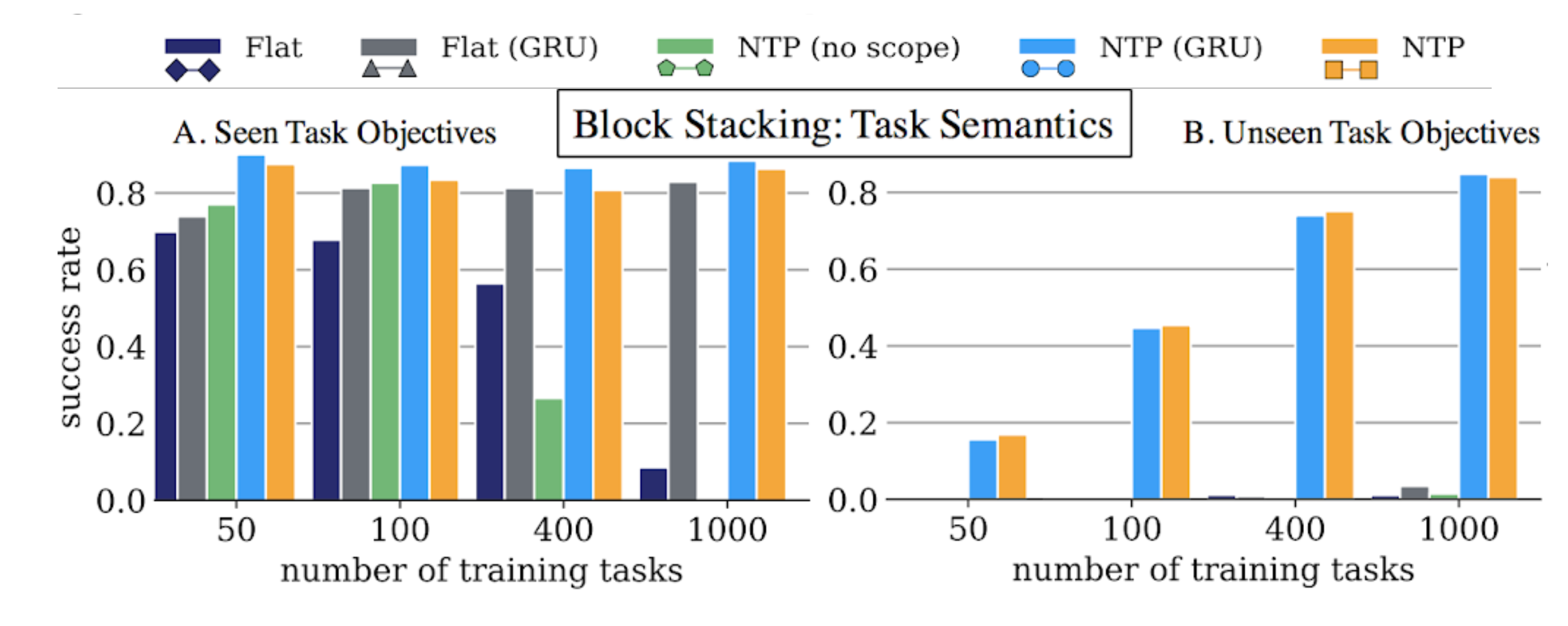

We start by the evaluation of the first approach we discussed: Neural Task Programming (NTP), where the model is supervised to do hierarchical decomposition. We compare four approaches here:

- Flat is a non-hierarchical model that takes as input task demonstration and current observation, and directly predicts the primitive APIs instead of calling hierarchical programs. It is important to understand the effect of learning hierarchical decomposition.

- Flat (GRU) is the Flat model with a GRU cell. In this case, we hope the internal memory can better learn the action (API) decision by leveraging dependencies between actions

- NTP (no scope) is a variant of the NTP model that feeds the entire demonstration to the subprograms, without recursively updating the scope of the demonstration to look at.

- NTP (GRU) is a complete NTP model with a GRU cell. This is to demonstrate that the reactive core network in NTP can better generalize to longer tasks and recover from unexpected failures due to noise, which is crucial in robot manipulation tasks.

Here the X-axis is the number of training tasks or block configurations we used for the model to learn hierarchical configuration. We generate 100 demonstrations for each of these training tasks. The Y-axis is the success rate if the model can successfully stack the blocks into the same configuration. On the left plot, we still test on block configurations that we used inside training, but just evaluating different initial configurations. That is, the blocks are initialized in different locations from training, but the provided single demonstration still stacks the blocks into a configuration we used in training. We can see that the Flat GRU model can still learn to memorize the configurations seen in training, and follow the given demonstration at test time. On the other hand, only NTP trained to do hierarchical decomposition is able to generalize to unseen configuration, as shown in the plot on the right.

We also tested the ability of NTP to respond to intermediate failures on the real robot and show that NTP can perform close-loop control:

We have seen that NTP is a general framework to hierarchically decompose task demonstrations. This learned decomposition allows NTP to generalize to new tasks based on a single demonstration. However, the main limitation is that the model still requires hundreds of tasks to learn a useful recursive decomposition.

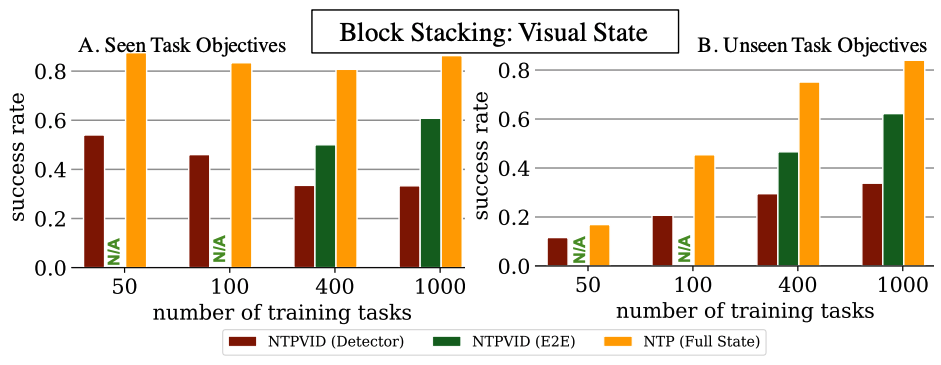

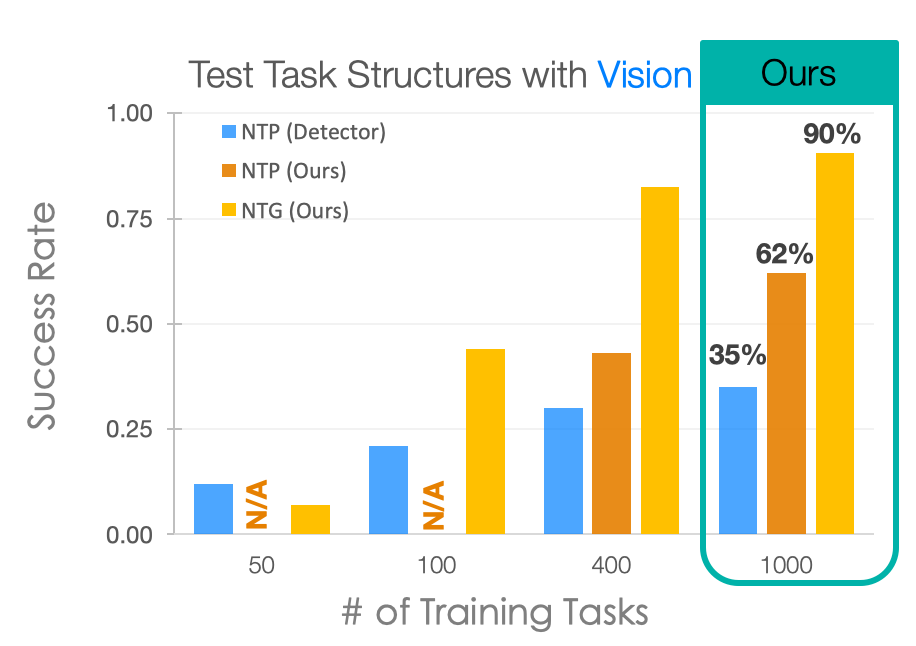

If the demonstrations are represented by raw pixel video frames (NTPVID, E2E, green bars) rather than object locations (NTP, Full State, yellow bars), we can see a significant drop in the performance fixing the amount of training tasks. Allowing visual input can be an important feature because object detection and pose estimation are themselves challenging problems. So, next we investigate if explicitly incorporating the compositional prior can improve the learning efficiency in this case. As previously discussed, Neural Task Graph Networks (NTG) uses the task graph as an intermediate representation and the compositional prior is directly used because the parsing of task graph from video and the execution based on task graph now both have to follow the graphical and compositional structure. In the plot below, we add in the performance of NTG on the same evaluation setting:

We can see that the best performance of NTP with visual input is just 62%. On the other hand, by explicitly using task graphs for composition, NTG is able to improve the performance by about 30%. This shows that NTG is able to learn new tasks with a single demonstration more efficiently. For NTP modules to achieve the same success rate, it would require much more training tasks than 1000 tasks.

In addition to improving learning efficiency, being able to learn from video and generate task graphs also lead to interesting applications and improve the interpretability of the model. We show that the task graph generator is able to generate task graphs from surgical videos from the JIGSAW dataset:

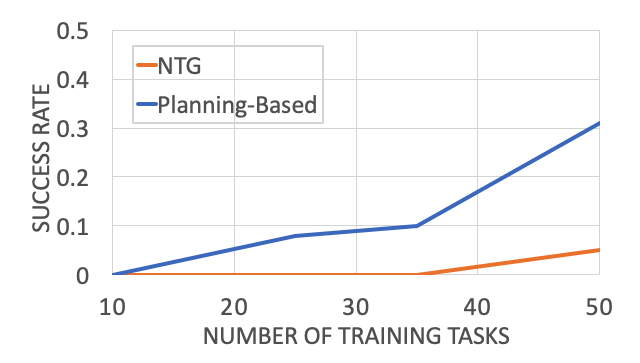

So we have seen that explicitly using task graphs can improve learning efficiency, but can we go even further? What can we do with more human domain knowledge? The main drive that is pushing us is the fact that even with compositionality we still need hundreds of training tasks to get a useful model. If we look at the performance plot of NTG, we can see that the success rate with 50 training tasks is around 10%. However, that is already 50 * 100 = 5000 training demonstrations we are using, which is quite a lot to collect for real-world tasks like assembly and cooking (cook 5000 dishes!).

Our planning-based formulation aims to address this by using the compositional prior as harder constraints. We provide a definition of how pick-and-place can be decomposed, and generally the rules constraining the condition that we can apply certain actions (e.g., can only pick up things when the robot hand is empty).

For example, here the goal is for Block A to be on top of Block B (On A B), and for Block A to have nothing on top of it (Clear A). Initially, nothing is on top of Block A (Clear A) and nothing is on top of Block B (Clear B). If we can solve the symbol grounding problem perfectly, then our model can perfectly reproduce the demonstrated task by searching. This allows us to push the performance further with less than 50 training tasks:

The planning-based formulation significantly outperforms NTG in this regime. And, this is not the only advantage of a planning-based formulation. The idea of inferring the goal or intention of a demonstration is itself an interesting problem! In addition, a planning-based or goal-based formulation also enables generalization to drastically different environments for robot execution. This is because all we need to learn from the demonstration is its goal or the intention or the demonstrator, and it poses no constraint on what the execution environment should be like.

Here, we demonstrate cooking tomato soup in a mockup kitchen with several distracting objects (like Cheez-It Box and Mustard Bottle), and our robot is able to cook the tomato soup in a real kitchen without being distracted by the irrelevant objects.

Summary

We discuss a challenging problem: one-shot imitation learning, where the goal is for a robot to learn new tasks based on a single demonstration of the task. We have presented several ways that we can use compositional prior to improve the model learning efficiency: hierarchical program decomposition, task graph representation, and the planning-based formulation. However, there are still many problems remaining to be solved. For example, how can we better integrate high-level action decision and planning with low-level motion planning and optimization? In this post, we only discuss approaches that decide what the robot should do at the high-level, like picking which object, but another important aspect of robotics is the lower-level question of how to actually pick up the object. And, there are all kinds of complicated interactions between them that we are working on to address. For more details, please refer to the following materials:

This blog post is based on the following paper:

- “Neural Task Programming: Learning to Generalize Across Hierarchical Tasks” by Danfei Xu*, Suraj Nair*, Yuke Zhu, Julian Gao, Animesh Garg, Li Fei-Fei, Silvio Savarese.

- “Neural Task Graphs: Generalizing to Unseen Tasks from a Single Video Demonstration” by De-An Huang*, Suraj Nair*, Danfei Xu*, Yuke Zhu, Animesh Garg, Li Fei-Fei, Silvio Savarese, Juan Carlos Niebles

- “Continuous Relaxation of Symbolic Planner for One-Shot Imitation Learning” by De-An Huang, Danfei Xu, Yuke Zhu, Animesh Garg, Silvio Savarese, Li Fei-Fei, Juan Carlos Niebles

- “Motion Reasoning for Goal-Based Imitation Learning” by De-An Huang, Yu-Wei Chao, Chris Paxton, Xinke Deng, Li Fei-Fei, Juan Carlos Niebles, Animesh Garg, Dieter Fox

Study finds stronger links between automation and inequality

This is part 3 of a three-part series examining the effects of robots and automation on employment, based on new research from economist and Institute Professor Daron Acemoglu.

Modern technology affects different workers in different ways. In some white-collar jobs — designer, engineer — people become more productive with sophisticated software at their side. In other cases, forms of automation, from robots to phone-answering systems, have simply replaced factory workers, receptionists, and many other kinds of employees.

Now a new study co-authored by an MIT economist suggests automation has a bigger impact on the labor market and income inequality than previous research would indicate — and identifies the year 1987 as a key inflection point in this process, the moment when jobs lost to automation stopped being replaced by an equal number of similar workplace opportunities.

“Automation is critical for understanding inequality dynamics,” says MIT economist Daron Acemoglu, co-author of a newly published paper detailing the findings.

Within industries adopting automation, the study shows, the average “displacement” (or job loss) from 1947-1987 was 17 percent of jobs, while the average “reinstatement” (new opportunities) was 19 percent. But from 1987-2016, displacement was 16 percent, while reinstatement was just 10 percent. In short, those factory positions or phone-answering jobs are not coming back.

“A lot of the new job opportunities that technology brought from the 1960s to the 1980s benefitted low-skill workers,” Acemoglu adds. “But from the 1980s, and especially in the 1990s and 2000s, there’s a double whammy for low-skill workers: They’re hurt by displacement, and the new tasks that are coming, are coming slower and benefitting high-skill workers.”

The new paper, “Unpacking Skill Bias: Automation and New Tasks,” will appear in the May issue of the American Economic Association: Papers and Proceedings. The authors are Acemoglu, who is an Institute Professor at MIT, and Pascual Restrepo PhD ’16, an assistant professor of economics at Boston University.

Low-skill workers: Moving backward

The new paper is one of several studies Acemoglu and Restrepo have conducted recently examining the effects of robots and automation in the workplace. In a just-published paper, they concluded that across the U.S. from 1993 to 2007, each new robot replaced 3.3 jobs.

In still another new paper, Acemoglu and Restrepo examined French industry from 2010 to 2015. They found that firms that quickly adopted robots became more productive and hired more workers, while their competitors fell behind and shed workers — with jobs again being reduced overall.

In the current study, Acemoglu and Restrepo construct a model of technology’s effects on the labor market, while testing the model’s strength by using empirical data from 44 relevant industries. (The study uses U.S. Census statistics on employment and wages, as well as economic data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Bureau of Labor Studies, among other sources.)

The result is an alternative to the standard economic modeling in the field, which has emphasized the idea of “skill-biased” technological change — meaning that technology tends to benefit select high-skilled workers more than low-skill workers, helping the wages of high-skilled workers more, while the value of other workers stagnates. Think again of highly trained engineers who use new software to finish more projects more quickly: They become more productive and valuable, while workers lacking synergy with new technology are comparatively less valued.

However, Acemoglu and Restrepo think even this scenario, with the prosperity gap it implies, is still too benign. Where automation occurs, lower-skill workers are not just failing to make gains; they are actively pushed backward financially. Moreover, Acemoglu and Restrepo note, the standard model of skill-biased change does not fully account for this dynamic; it estimates that productivity gains and real (inflation-adjusted) wages of workers should be higher than they actually are.

More specifically, the standard model implies an estimate of about 2 percent annual growth in productivity since 1963, whereas annual productivity gains have been about 1.2 percent; it also estimates wage growth for low-skill workers of about 1 percent per year, whereas real wages for low-skill workers have actually dropped since the 1970s.

“Productivity growth has been lackluster, and real wages have fallen,” Acemoglu says. “Automation accounts for both of those.” Moreover, he adds, “Demand for skills has gone down almost exclusely in industries that have seen a lot of automation.”

Why “so-so technologies” are so, so bad

Indeed, Acemoglu says, automation is a special case within the larger set of technological changes in the workplace. As he puts it, automation “is different than garden-variety skill-biased technological change,” because it can replace jobs without adding much productivity to the economy.

Think of a self-checkout system in your supermarket or pharmacy: It reduces labor costs without making the task more efficient. The difference is the work is done by you, not paid employees. These kinds of systems are what Acemoglu and Restrepo have termed “so-so technologies,” because of the minimal value they offer.

“So-so technologies are not really doing a fantastic job, nobody’s enthusiastic about going one-by-one through their items at checkout, and nobody likes it when the airline they’re calling puts them through automated menus,” Acemoglu says. “So-so technologies are cost-saving devices for firms that just reduce their costs a little bit but don’t increase productivity by much. They create the usual displacement effect but don’t benefit other workers that much, and firms have no reason to hire more workers or pay other workers more.”

To be sure, not all automation resembles self-checkout systems, which were not around in 1987. Automation at that time consisted more of printed office records being converted into databases, or machinery being added to sectors like textiles and furniture-making. Robots became more commonly added to heavy industrial manufacturing in the 1990s. Automation is a suite of technologies, continuing today with software and AI, which are inherently worker-displacing.

“Displacement is really the center of our theory,” Acemoglu says. “And it has grimmer implications, because wage inequality is associated with disruptive changes for workers. It’s a much more Luddite explanation.”

After all, the Luddites — British textile mill workers who destroyed machinery in the 1810s — may be synonymous with technophobia, but their actions were motivated by economic concerns; they knew machines were replacing their jobs. That same displacement continues today, although, Acemoglu contends, the net negative consequences of technology on jobs is not inevitable. We could, perhaps, find more ways to produce job-enhancing technologies, rather than job-replacing innovations.

“It’s not all doom and gloom,” says Acemoglu. “There is nothing that says technology is all bad for workers. It is the choice we make about the direction to develop technology that is critical.”