TL;DR: We are launching a NeurIPS competition and benchmark called BASALT: a

set of Minecraft environments and a human evaluation protocol that we hope will

stimulate research and investigation into solving tasks with no pre-specified

reward function, where the goal of an agent must be communicated through

demonstrations, preferences, or some other form of human feedback. Sign up

to participate in the

competition!

Motivation

Deep reinforcement learning takes a reward function as input and learns to

maximize the expected total reward. An obvious question is: where did this

reward come from? How do we know it captures what we want? Indeed, it often

doesn’t capture what we want, with

many

recent

examples showing that the provided

specification often leads the agent to behave in an unintended way.

Our existing algorithms have a problem: they implicitly assume access to a

perfect specification, as though one has been handed down by God. Of course, in

reality, tasks don’t come pre-packaged with rewards; those rewards come from

imperfect human reward designers.

For example, consider the task of summarizing articles. Should the agent focus

more on the key claims, or on the supporting evidence? Should it always use a

dry, analytic tone, or should it copy the tone of the source material? If the

article contains toxic content, should the agent summarize it faithfully,

mention that toxic content exists but not summarize it, or ignore it completely?

How should the agent deal with claims that it knows or suspects to be false? A

human designer likely won’t be able to capture all of these considerations in a

reward function on their first try, and, even if they did manage to have a

complete set of considerations in mind, it might be quite difficult to translate

these conceptual preferences into a reward function the environment can directly

calculate.

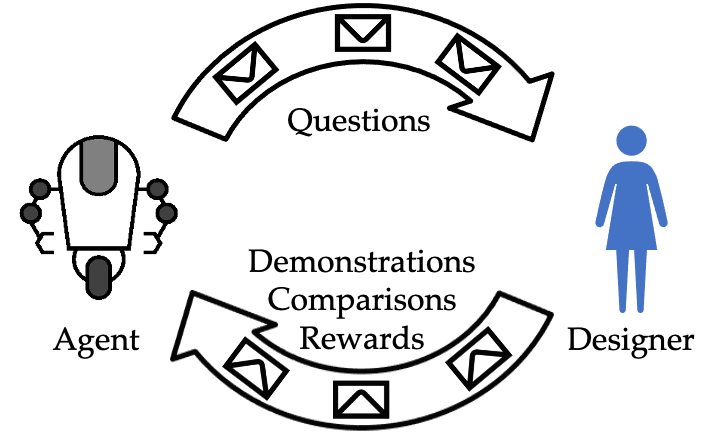

Since we can’t expect a good specification on the first try, much recent work

has proposed algorithms that instead allow the designer to iteratively

communicate details and preferences about the task. Instead of rewards, we use

new types of feedback, such as

demonstrations (in the above example,

human-written summaries), preferences

(judgments about which of two summaries is better),

corrections (changes

to a summary that would make it better), and more. The agent may

also

elicit

feedback by, for example, taking the first

steps of a provisional plan and seeing if the human intervenes, or by asking the

designer questions about the task. This

paper provides a framework and summary of

these techniques.

Despite the plethora of techniques developed to tackle this problem, there have

been no popular benchmarks that are specifically intended to evaluate algorithms

that learn from human feedback. A typical paper will take an existing deep RL

benchmark (often Atari or MuJoCo), strip away the rewards, train an agent using

their feedback mechanism, and evaluate performance according to the preexisting

reward function.

This has a variety of problems, but most notably, these environments do not have

many potential goals. For example, in the Atari game Breakout, the agent must

either hit the ball back with the paddle, or lose. There are no other

options. Even if you get good performance on Breakout with your algorithm, how

can you be confident that you have learned that the goal is to hit the bricks

with the ball and clear all the bricks away, as opposed to some simpler

heuristic like “don’t die”? If this algorithm were applied to summarization,

might it still just learn some simple heuristic like “produce grammatically

correct sentences”, rather than actually learning to summarize? In the real

world, you aren’t funnelled into one obvious task above all others; successfully

training such agents will require them being able to identify and perform a

particular task in a context where many tasks are possible.

We built the Benchmark for Agents that Solve Almost Lifelike Tasks (BASALT) to

provide a benchmark in a much richer environment: the popular video game

Minecraft. In Minecraft, players can choose among

a wide variety of things to do. Thus, to learn to do a specific task in

Minecraft, it is crucial to learn the details of the task from human feedback;

there is no chance that a feedback-free approach like “don’t die” would perform

well.

We’ve just launched the MineRL BASALT competition on Learning from Human

Feedback, as a sister competition to the existing

MineRL Diamond competition on Sample Efficient Reinforcement

Learning, both of which will be presented at

NeurIPS 2021. You can sign up to participate in the competition

here.

Our aim is for BASALT to mimic realistic settings as much as possible, while

remaining easy to use and suitable for academic experiments. We’ll first explain

how BASALT works, and then show its advantages over the current environments

used for evaluation.

What is BASALT?

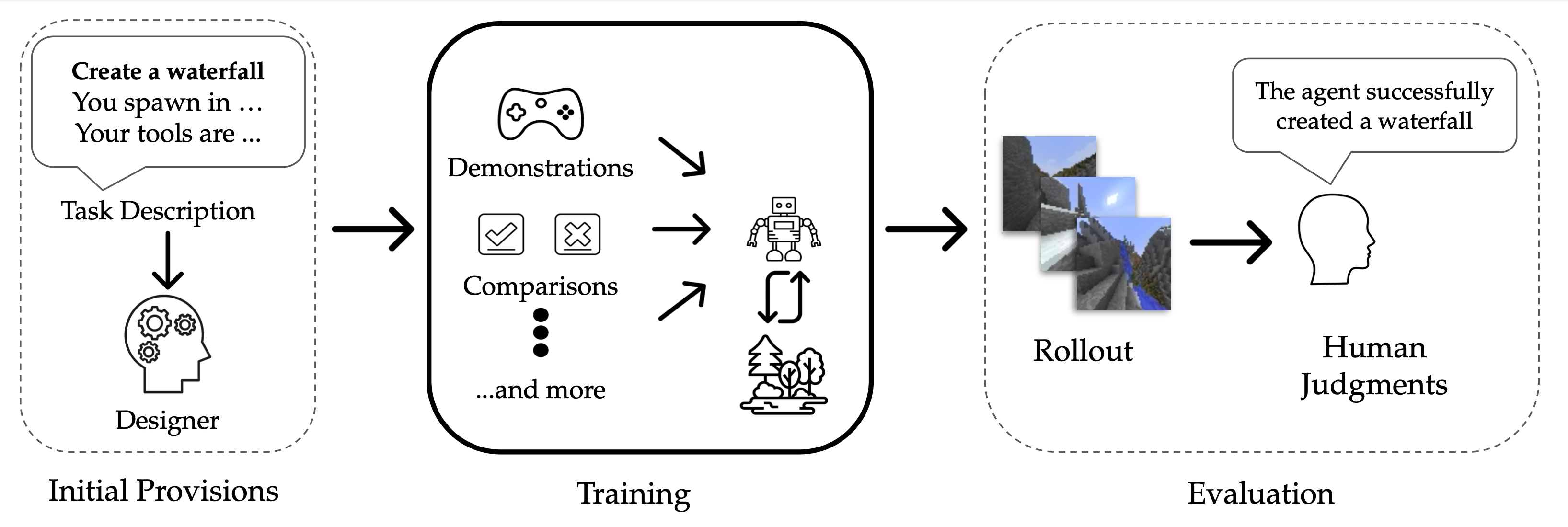

We argued previously that we should be thinking about the specification of the

task as an iterative process of imperfect communication between the AI designer

and the AI agent. Since BASALT aims to be a benchmark for this entire process,

it specifies tasks to the designers and allows the designers to develop agents

that solve the tasks with (almost) no holds barred.

Initial provisions. For each task, we provide a Gym environment (without

rewards), and an English description of the task that must be

accomplished. The Gym environment exposes pixel observations as well as

information about the player’s inventory. Designers may then use whichever

feedback modalities they prefer, even reward functions and hardcoded

heuristics, to create agents that accomplish the task. The only restriction is

that they may not extract additional information from the Minecraft

simulator, since this approach would not be possible in most real world

tasks.

For example, for the MakeWaterfall

task,

we provide the following details:

Description: After spawning in a mountainous area, the agent should build

a beautiful waterfall and then reposition itself to take a scenic picture of

the same waterfall. The picture of the waterfall can be taken by orienting

the camera and then throwing a snowball when facing the waterfall at a good

angle.

Resources: 2 water buckets, stone pickaxe, stone shovel, 20 cobblestone blocks

Evaluation. How do we evaluate agents if we don’t provide reward functions?

We rely on human comparisons. Specifically, we record the trajectories of

two different agents on a particular environment seed and ask a human to

decide which of the agents performed the task better. We plan to release code

that will allow researchers to collect these comparisons from Mechanical Turk

workers. Given a few comparisons of this form, we use

TrueSkill to compute scores for

each of the agents that we are evaluating.

For the competition, we will hire contractors to provide the comparisons. Final

scores are determined by averaging normalized TrueSkill scores across tasks. We

will validate potential winning submissions by retraining the models and

checking that the resulting agents perform similarly to the submitted agents.

Dataset. While BASALT does not place any restrictions on what types of

feedback may be used to train agents, we (and MineRL

Diamond) have found that, in practice,

demonstrations are needed at the start of training to get a reasonable

starting policy. (This approach has also been used for

Atari.) Therefore, we have collected and

provided a dataset of human demonstrations for each of our tasks.

The three stages of the waterfall task in one of our demonstrations: climbing to

a good location, placing the waterfall, and returning to take a scenic picture

of the waterfall.

Getting started. One of our goals was to make BASALT particularly easy to

use. Creating a BASALT environment is as simple as installing

MineRL and calling gym.make() on the appropriate

environment name. We have also provided a behavioral cloning (BC) agent in a

repository

that could be submitted to the competition; it takes just a couple of hours to

train an agent on any given task.

Advantages of BASALT

BASALT has a number of advantages over existing benchmarks like MuJoCo and Atari:

Many reasonable goals. People do a lot of things in Minecraft: perhaps you

want to defeat the Ender Dragon while others try to stop

you, or build a giant floating

island chained to the ground, or

produce more stuff than you will ever

need. This is a particularly

important property for a benchmark where the point is to figure out what to

do: it means that human feedback is critical in identifying which task the

agent must perform out of the many, many tasks that are possible in

principle.

Existing benchmarks mostly do not satisfy this property:

- In some Atari games, if you do anything other than the intended gameplay, you

die and reset to the initial state, or you get stuck. As a result, even pure

curiosity-based agents do well on

Atari. - Similarly in MuJoCo, there is not much that any given simulated robot can

do. Unsupervised skill learning methods will frequently learn policies that

perform well on the true reward: for example,

DADS learns locomotion policies for MuJoCo

robots that would get high reward, without using any reward information or human

feedback.

In contrast, there is effectively no chance of such an unsupervised method

solving BASALT tasks. When testing your algorithm with BASALT, you don’t have to

worry about whether your algorithm is secretly learning a heuristic like

curiosity that wouldn’t work in a more realistic setting.

In Pong, Breakout and Space Invaders, you either play towards winning the game,

or you die.

In Minecraft, you could battle the Ender Dragon, farm peacefully, practice

archery, and more.

Large amounts of diverse data. Recent

work has demonstrated the value of large

generative models trained on huge, diverse datasets. Such models may offer a

path forward for specifying tasks: given a large pretrained model, we can

“prompt” the model with an input such that the model then generates the

solution to our task. BASALT is an excellent test suite for such an approach,

as there are thousands of hours of Minecraft gameplay on YouTube.

In contrast, there is not much easily available diverse data for Atari or

MuJoCo. While there may be videos of Atari gameplay, in most cases these are all

demonstrations of the same task. This makes them less suitable for studying the

approach of training a large model with broad knowledge and then “targeting” it

towards the task of interest.

Robust evaluations. The environments and reward functions used in current

benchmarks have been designed for reinforcement learning, and so often include

reward shaping or termination conditions that make them unsuitable for

evaluating algorithms that learn from human feedback. It is often possible to

get surprisingly good performance with hacks that would never work in a

realistic setting. As an extreme example, Kostrikov et

al show that when initializing the GAIL

discriminator to a constant value (implying the constant reward

$R(s,a) = log 2$), they reach 1000 reward on Hopper, corresponding to about a

third of expert performance – but the resulting policy stays still and doesn’t

do anything!

In contrast, BASALT uses human evaluations, which we expect to be far more

robust and harder to “game” in this way. If a human saw the Hopper staying still

and doing nothing, they would correctly assign it a very low score, since it is

clearly not progressing towards the intended goal of moving to the right as fast

as possible.

No holds barred. Benchmarks often have some strategies that are implicitly

not allowed because they would “solve” the benchmark without actually solving

the underlying problem of interest. For example, there is

controversy over

whether algorithms should be allowed to rely on determinism in Atari, as many

such solutions would likely not work in more realistic settings.

However, this is an effect to be minimized as much as possible: inevitably, the

ban on strategies will not be perfect, and will likely exclude some strategies

that really would have worked in realistic settings. We can avoid this problem

by having particularly challenging tasks, such as playing Go or building

self-driving cars, where any method of solving the task would be impressive and

would imply that we had solved a problem of interest. Such benchmarks are “no

holds barred”: any approach is acceptable, and thus researchers can focus

entirely on what leads to good performance, without having to worry about

whether their solution will generalize to other real world tasks.

BASALT does not quite reach this level, but it is close: we only ban strategies

that access internal Minecraft state. Researchers are free to hardcode

particular actions at particular timesteps, or ask humans to provide a novel

type of feedback, or train a large generative model on YouTube data, etc. This

enables researchers to explore a much larger space of potential approaches to

building useful AI agents.

Harder to “teach to the test”. Suppose Alice is training an imitation

learning algorithm on HalfCheetah, using 20 demonstrations. She suspects that

some of the demonstrations are making it hard to learn, but doesn’t know which

ones are problematic. So, she runs 20 experiments. In the ith experiment, she

removes the ith demonstration, runs her algorithm, and checks how much reward

the resulting agent gets. From this, she realizes she should remove

trajectories 2, 10, and 11; doing this gives her a 20% boost.

The problem with Alice’s approach is that she wouldn’t be able to use this

strategy in a real-world task, because in that case she can’t simply “check how

much reward the agent gets” – there isn’t a reward function to check! Alice is

effectively tuning her algorithm to the test, in a way that wouldn’t generalize

to realistic tasks, and so the 20% boost is illusory.

While researchers are unlikely to exclude specific data points in this way, it

is common to use the test-time reward as a way to validate the algorithm and

to tune hyperparameters, which can have the same effect. This

paper quantifies a similar effect in few-shot

learning with large language models, and finds that previous few-shot learning

claims were significantly overstated.

BASALT ameliorates this problem by not having a reward function in the first

place. It is of course still possible for researchers to teach to the test

even in BASALT, by running many human evaluations and tuning the algorithm based

on these evaluations, but the scope for this is greatly reduced, since it is far

more costly to run a human evaluation than to check the performance of a trained

agent on a programmatic reward.

Note that this does not prevent all hyperparameter tuning. Researchers can still

use other strategies (that are more reflective of realistic settings), such as:

- Running preliminary experiments and looking at proxy metrics. For example,

with behavioral cloning (BC), we could perform hyperparameter tuning to reduce

the BC loss. - Designing the algorithm using experiments on environments which do have

rewards (such as the MineRL Diamond environments).

Easily available experts. Domain experts can usually be consulted when an AI

agent is built for real-world deployment. For example, the NET-VISA

system used for

global seismic monitoring was built with relevant domain knowledge provided by

geophysicists. It would thus be useful to investigate techniques for building

AI agents when expert help is available.

Minecraft is well suited for this because it is extremely popular, with over

100 million active players. In addition, many of its properties are easy to

understand: for example, its tools have similar functions to real world tools,

its landscapes are somewhat realistic, and there are easily understandable goals

like building shelter and acquiring enough food to not starve. We ourselves have

hired Minecraft players both through Mechanical Turk and by recruiting Berkeley

undergrads.

Building towards a long-term research agenda. While BASALT currently focuses

on short, single-player tasks, it is set in a world that contains many avenues

for further work to build general, capable agents in Minecraft. We envision

eventually building agents that can be instructed to perform arbitrary

Minecraft tasks in natural language on public multiplayer servers, or

inferring what large scale project human players are working on and assisting

with those projects, while adhering to the norms and customs followed on that

server.

Can we build an agent that can help recreate Middle Earth on MCME (left), and also play Minecraft

on the anarchy server 2b2t

(right) on which large-scale destruction of property (“griefing”) is the norm?

Interesting research questions

Since BASALT is quite different from past benchmarks, it allows us to study a

wider variety of research questions than we could before. Here are some

questions that seem particularly interesting to us:

- How do various feedback modalities compare to each other? When should each

one be used? For example, current practice tends to train on demonstrations

initially and preferences later. Should other feedback modalities be integrated

into this practice? - Are corrections an effective technique for focusing the agent on rare but

important actions? For example, vanilla behavioral cloning on MakeWaterfall leads

to an agent that moves near waterfalls but doesn’t create waterfalls of its own,

presumably because the “place waterfall” action is such a tiny fraction of the

actions in the demonstrations. Intuitively, we would like a human to “correct”

these problems, e.g. by specifying when in a trajectory the agent should have

taken a “place waterfall” action. How should this be implemented, and how

powerful is the resulting technique? (The

past

work we are aware of does not seem directly

applicable, though we have not done a thorough literature review.) - How can we best leverage domain expertise? If for a given task, we have (say)

five hours of an expert’s time, what is the best use of that time to train a

capable agent for the task? What if we have a hundred hours of expert time

instead? - Would the “GPT-3 for Minecraft” approach work well for BASALT? Is it

sufficient to simply prompt the model appropriately? For example, a sketch of

such an approach would be:- Create a dataset of YouTube videos paired with their automatically

generated captions, and train a model that predicts the next video frame from

previous video frames and captions. - Train a policy that takes actions which lead to observations predicted by

the generative model (effectively learning to imitate human behavior,

conditioned on previous video frames and the caption). - Design a “caption prompt” for each BASALT task that induces the policy to

solve that task.

- Create a dataset of YouTube videos paired with their automatically

FAQ

If there are really no holds barred, couldn’t participants record themselves

completing the task, and then replay those actions at test time?

Participants wouldn’t be able to use this strategy because we keep the seeds of

the test environments secret. More generally, while we allow participants to

use, say, simple nested-if strategies, Minecraft worlds are sufficiently random

and diverse that we expect that such strategies won’t have good performance,

especially given that they have to work from pixels.

Won’t it take far too long to train an agent to play Minecraft? After all, the

Minecraft simulator must be really slow relative to MuJoCo or Atari.

We designed the tasks to be in the realm of difficulty where it should be

feasible to train agents on an academic budget. Our behavioral cloning baseline

trains in a couple of hours on a single GPU. Algorithms that require environment

simulation like GAIL will take longer, but we expect that a day or two of

training will be enough to get decent results (during which you can get a few

million environment samples).

Won’t this competition just reduce to “who can get the most compute and human

feedback”?

We impose limits on the amount of compute and human feedback that submissions

can use to prevent this scenario. We will retrain the models of any potential

winners using these budgets to verify adherence to this rule.

Conclusion

We hope that BASALT will be used by anyone who aims to learn from human

feedback, whether they are working on imitation learning, learning from

comparisons, or some other method. It mitigates many of the issues with the

standard benchmarks used in the field. The current baseline has lots of obvious

flaws, which we hope the research community will soon fix.

Note that, so far, we have worked on the competition version of BASALT. We aim

to release the benchmark version shortly. You can get started now, by simply

installing MineRL from pip and loading up the BASALT

environments. The code to run your own human evaluations will be added in the

benchmark release.

If you would like to use BASALT in the very near future and would like beta

access to the evaluation code, please email the lead organizer, Rohin Shah, at

rohinmshah@berkeley.edu.

This post is based on the paper “The MineRL BASALT Competition on Learning

from Human Feedback”, accepted at the NeurIPS

2021 Competition Track. Sign up to participate in the

competition!