Many tasks that we do on a regular basis, such as navigating a city, cooking a

meal, or loading a dishwasher, require planning over extended periods of time.

Accomplishing these tasks may seem simple to us; however, reasoning over long

time horizons remains a major challenge for today’s Reinforcement Learning (RL)

algorithms. While unable to plan over long horizons, deep RL algorithms excel

at learning policies for short horizon tasks, such as robotic grasping,

directly from pixels. At the same time, classical planning methods such as

Dijkstra’s algorithm and A$^*$ search can plan over long time horizons, but

they require hand-specified or task-specific abstract representations of the

environment as input.

To achieve the best of both worlds, state-of-the-art visual navigation methods

have applied classical search methods to learned graphs. In particular, SPTM [2]

and SoRB [3] use a replay buffer of observations as nodes in a graph and learn

a parametric distance function to draw edges in the graph. These methods have

been successfully applied to long-horizon simulated navigation tasks that were

too challenging for previous methods to solve.

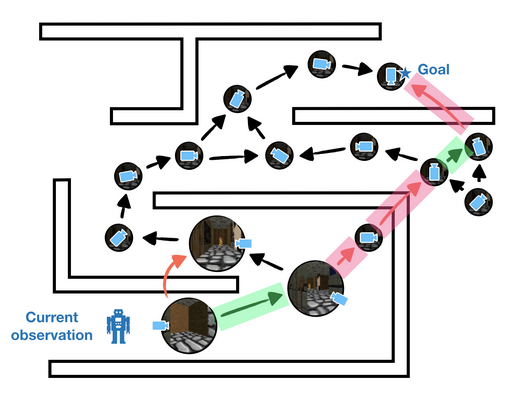

Nevertheless, these methods are still limited because they are highly sensitive

to errors in the learned graph. Even a single faulty edge acts like a wormhole

in the graph topology that planning algorithms try to exploit, which makes

existing methods that combine graph search and RL extremely brittle. For

example, if an artificial agent navigating a maze thinks that two observations

on either side of a wall are nearby, its plans will involve transitions that

collide into the wall. Adopting a simple model that assumes a constant

probability $p$ of each edge being faulty, we see that the expected number of

faulty edges is $p|E| = O(|V|^2)$. In other words, errors in the graph scale

quadratically with the number of nodes in the graph.

We could do a lot better if we could minimize the errors in the graph. But how?

Graphs over observations in both simulated and real-world environments can be

prohibitively large, making it challenging to even identify which edges are

faulty. To minimize errors in the graph, then, we desire sparsity; we want to

keep a minimal set of nodes that is sufficient for planning. If we have a way

to aggregate similar observations into a single node in the graph, we can

reduce the number of errors and improve the accuracy of our plans. The key

challenge is to aggregate observations in a way that respects temporal

constraints. If observations are similar in appearance but actually far away,

then they should be aggregated into different nodes.

So how can we sparsify our graph while guaranteeing that the graph remains

useful for planning? Our key insight is a novel merging criterion called

two-way consistency. Two-way consistency can be viewed as a generalization of

value irrelevance to the goal-conditioned setting. Intuitively, two-way consistency

merges nodes (i) that can be interchanged as starting states and (ii) that can be

interchanged as goal states.

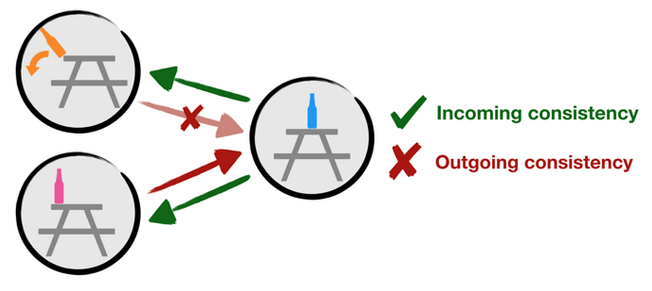

For an example of two-way consistency, consider the above figure. Suppose

during our node merging procedure we ask: can we merge the nodes with pink and

orange bottles according to two-way consistency? First, we note that moving

from the blue bottle to the pink bottle requires roughly the same work as

moving from the blue bottle to the orange bottle. So the nodes with pink and

orange bottles satisfy criterion (ii) because they can be interchanged as goal

states. However, while it is possible to start from the pink bottle and move to

the blue bottle, if we instead start at the orange bottle, the orange bottle

will fall to the floor and crash! So the nodes with pink and orange bottles

fail criterion (i) because they cannot be interchanged as starting states.

In practice, we can’t expect to encounter two nodes that can be perfectly

interchanged. Instead, we merge nodes that can be interchanged up to a

threshold parameter $tau$. By increasing $tau$, we can make the resulting

graph as sparse as we’d like. Crucially, *we prove in the paper that merging

according to two-way consistency preserves the graph’s quality up to an error

term that scales only linearly with the merging threshold $tau$.

Our motivation for sparsity, discussed above, is robustness: we expect smaller

graphs to have fewer errors. Furthermore, our main theorem tells us that we can

merge nodes according to two-way consistency while preserving the graph’s

quality. Experimentally, though, are the resulting sparse graphs more robust?

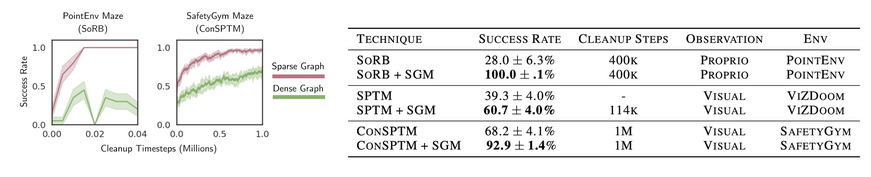

To test the robustness of Sparse Graphical Memory to errors in learned distance

metrics, we thinned the walls in the PointEnv mazes of [3]. While PointEnv is a

simple environment with $(x, y)$ coordinate observations, thinning the walls is

a major challenge for parametric distance functions; any error in the learned

distance function will cause faulty edges across the walls that destroy the

feasibility of plans. For this reason, simply thinning the maze walls is enough

to break the previous state-of-the-art [3] resulting in a 0% success rate.

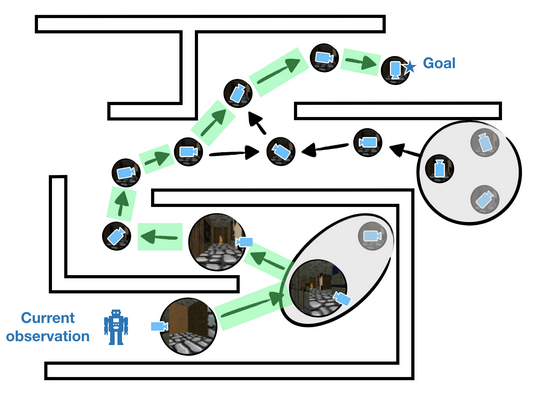

How does Sparse Graphical Memory fare? With many fewer edges, it becomes

tractable to perform self-supervised cleanup: the agent can step through the

environment to detect and remove faulty edges from its graph. The below figure

illustrates the results of this process. While the dense graph shown in red has

many faulty edges, sparsity and self-supervised cleanup, shown in green,

overcome errors in the learned distance metric, leading to a 100% success rate.

We see a similar trend in experiments with visual input. In both ViZDoom [4]

and SafetyGym [5] – maze navigation tasks that require planning from raw

images – Sparse Graphical Memory consistently improves the success of baseline

methods including SoRB [3] and SPTM [2].

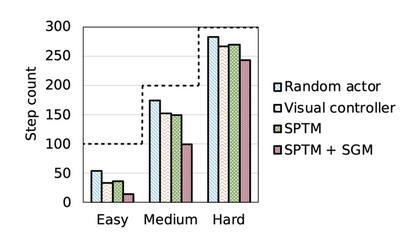

In addition to containing fewer errors, Sparse Graphical Memory also results in

more optimal plans. On a ViZDoom maze navigation task [4], we find that SGM

requires significantly less steps to reach the final goal across easy, medium,

and hard maze tasks, meaning that the agent follows a shorter path to the final

destination.

Overall, we found that state aggregation with two-way consistency resulted in

substantially more robust plans over the prior state-of-the-art. While

promising, many open questions and challenges remain for combining classical

planning with learning-based control. Some of the questions we’re thinking

about are – how can we extend these methods beyond navigation to manipulation

domains? As the world is not static, how should we build graphs over changing

environments? How can two-way consistency be utilized beyond the scope of

graphical-based planning methods? We are excited about these future directions

and hope our theoretical and experimental findings prove useful to other

researchers investigating control over extended time horizons.

References

- Emmons*, Jain*, Laskin* et al. Sparse Graphical Memory for Robust Planning. NeurIPS 2020.

- Savinov et al. Semi-parametric Topological Memory for Navigation. ICLR 2019.

- Eysenbach et al. Search on the Replay Buffer: Bridging Planning and Reinforcement Learning. NeurIPS 2020.

- Wydmuch et al. ViZDoom Competitions: Playing Doom from Pixels. IEEE Transactions on Games, 2018.

- Ray et al. Benchmarking Safe Exploration in Deep Reinforcement Learning. Preprint, 2019.