Speculative decoding is an optimization technique for inference that makes educated guesses about future tokens while generating the current token, all within a single forward pass. It incorporates a verification mechanism to ensure the correctness of these speculated tokens, thereby guaranteeing that the overall output of speculative decoding is identical to that of vanilla decoding. Optimizing the cost of inference of large language models (LLMs) is arguably one of the most critical factors in reducing the cost of generative AI and increasing its adoption. Towards this goal, various inference optimization techniques are available, including custom kernels, dynamic batching of input requests, and quantization of large models.

In this blog post, we provide a guide to speculative decoding and demonstrate how it can coexist with other optimizations. We are proud to open source the following, which includes the first speculator for Llama3 models:

- Speculator models for Meta Llama3 8B, IBM Granite 7B lab, Meta Llama2 13B, and Meta Code Llama2 13B.

- The code for inference via IBM’s fork of HF TGI.

- The code for training your own speculators and corresponding recipes.

We have deployed these speculators in an internal production-grade environment with thousands of daily users and observed 2x speedup on language models – Llama3 8B, Llama2 13B, and IBM Granite 7B and 3x speedup on IBM’s Granite 20B code models. We provide a detailed explanation of our approach in this technical report and are planning in-depth analysis in an upcoming ArXiv paper.

Speculative decoding: Inference

We run IBM TGIS in our internal production environment that has optimizations such as continuous batching, fused kernels, and quantization kernels. To enable speculative decoding in TGIS, we modified the paged attention kernel from vLLM. In what follows, we will describe the key changes to the inference engine to enable speculative decoding.

Speculative decoding is based on the premise that the model is powerful enough to predict multiple tokens in a single forward pass. However, the current inference servers are optimized to predict only a single token at a time. In our approach, we attach multiple speculative heads (in addition to the usual one) to the LLM to predict N+1-, N+2-, N+3-th … token. For example, 3 heads will predict 3 additional tokens. Details of the speculator architecture are explained in a later part of this blog. There are two challenges to achieve efficiency and correctness during inference – one is to predict without replicating KV-cache and the other is to verify that the predictions match the original model’s outcomes.

In a typical generation loop, after the prompt is processed in a single forward step, a sequence length of 1 (next token predicted) is fed into the forward pass of the model along with the kv-cache. In a naive speculative decoding implementation, each speculative head would have its own kv-cache, but instead we modify the paged attention kernel developed in the vLLM project to enable efficient kv-cache maintenance. This ensures that throughput does not reduce at larger batch sizes. Further, we modify the attention masks to enable verification of the N+1’th token and thus enable speculative decoding without deviating from the original model’s output. The details of this implementation are captured here.

Results

We illustrate the speedup obtained with the Meta’s chat versions of Llama2 13B using a simple prompt.

Figure 2: Visual illustration of the non-speculative generation (left) compared to speculative generation (right)

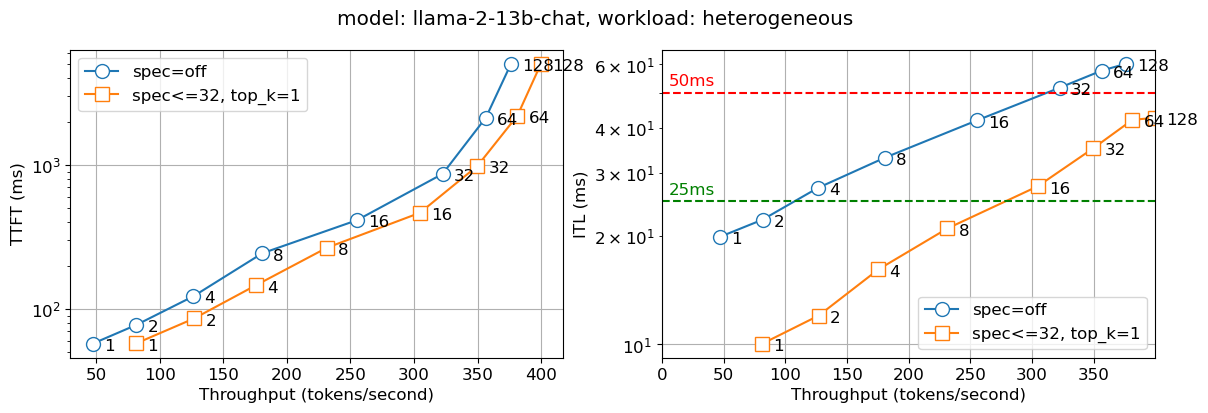

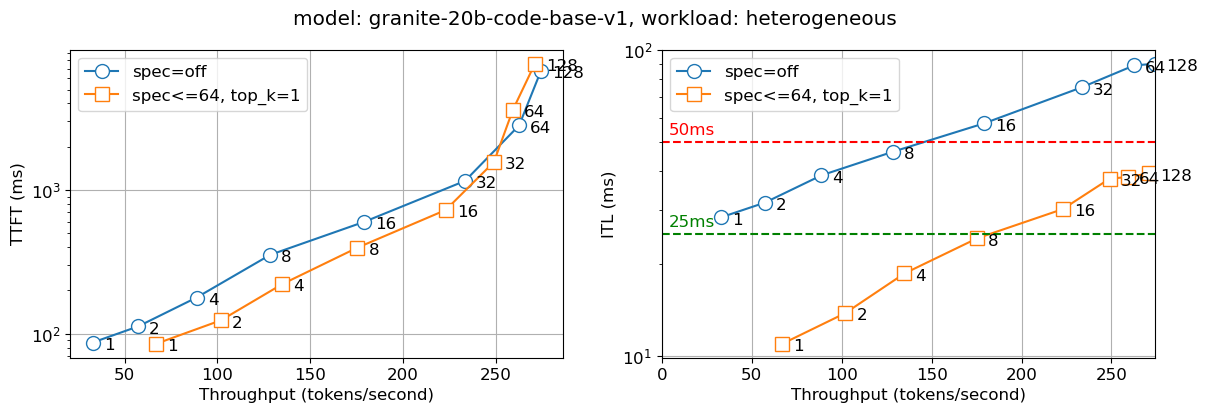

We deployed the above solution in an internal production environment. The figure below reports two metrics – time to first token (TTFT) and inter-token latency (ITL) with different numbers of concurrent users (which is captured in the numbers on the graph lines). We observe that the speculative decoding version is nearly twice as fast for the Llama2 13B chat model and nearly thrice as fast for the Granite 20B code model compared to the non-speculative version for all batch sizes. We observe similar behavior for the smaller models – IBM’s Granite 7B and Meta Llama3 8B models.

Figure 3: Time to first token (TTFT – left) and Inter-token latency (ITL – right) for Llama 13B with number of concurrent users indicated on the graph

Figure 4: Time to first token (TTFT – left) and Inter-token latency (ITL – right) for Granite 20B Code with number of concurrent users indicated on the graph

Note on efficiency

We performed numerous experiments to determine the right configuration for speculator training. These are:

- Speculator architecture: The current approach allows for the number of heads to be modified, which maps to the number of tokens that we can look ahead. Increasing the number of heads also increases the amount of extra compute needed and complexity of training. In practice, for language models, we find 3-4 heads works well in practice, whereas we found that code models can reap benefits from 6-8 heads.

- Compute: Increasing the number of heads results in increased compute in two dimensions, one is that of increased latency for a single forward pass as well as the compute needed for multiple tokens. If the speculator is not accurate with more heads, it will result in wasted compute increasing the latency and reducing the throughput.

- Memory: The increased compute is offset by the roundtrips to HBM that need to be done for each forward pass. Note that if we get 3 tokens lookahead correct, we have saved three round trip times on HBM.

We settled on 3-4 heads for the language models and 6-8 heads for the code models and across different model sizes ranging from 7B to 20B, we observed significant latency improvements without throughput loss compared to non-speculative decoding. We begin to observe throughput reduction beyond a batch size of 64, which happens rarely in practice.

Speculative decoding: Training

There are two broad approaches for speculative decoding, one is to leverage a smaller model (e.g., Llama 7B as a speculator for Llama 70B) and the other is to attach speculator heads (and train them). In our experiments, we find the approach of attaching speculator heads to be more effective both in model quality and latency gains.

Speculator architecture

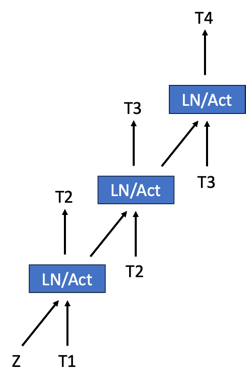

Medusa made speculative decoding popular; their approach is to add a head to the existing model which is then trained to do speculation. We modify the Medusa architecture by making the “heads” hierarchical, where each head stage predicts a single token and then feeds it to the next head stage. These multi-stage heads are depicted in the below figure. We are exploring ways of minimizing the embeddings table by sharing these across the multiple stages and base model.

Figure 4: A simple architecture diagram for a 3-headed multi-stage speculator. Z is the state from the base model.

Speculator training

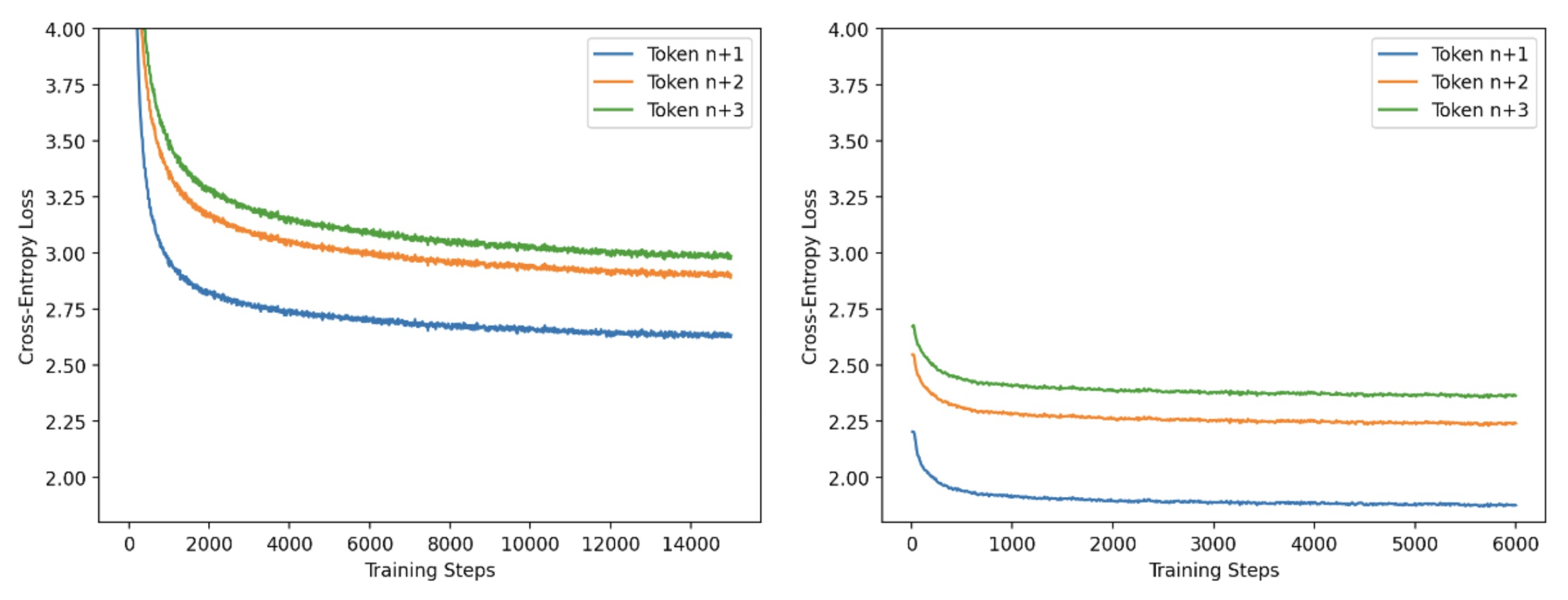

We have a two-phase approach to training a speculator for efficiency reasons. In the first phase, we train on small batches with long sequence lengths (4k tokens) and use the standard causal LM approach for training. In phase 2, we use large batches with short sequence lengths (256 tokens) generated from the base model. In this training phase, we tune the heads to match the output of the base model. Through numerous experiments, we find that a 5:2 ratio of steps for phase 1 vs phase 2 works well. We depict the progress of these phases in the below figure. We use PyTorch FSDP and IBM FMS for the training of speculators.

Figure 5: Per-head training loss curves for Llama2-13B speculator training, phase 1 and 2

Conclusion and Future Work

Through this blog, we are releasing a new approach for speculative decoding and the following assets:

- Models for improving the inter-token latencies for a range of models – Llama3 8B, Llama2 13B, Granite 7B, and CodeLlama 13B

- Production quality code for inference

- Recipes for training speculators

We are working on training speculators for Llama3 70B and Mistral models and invite the community to contribute as well as help improve on our framework. We would also love to work with major open source serving frameworks such as vLLM and TGI to contribute back our speculative decoding approach to benefit the community.

Acknowledgements

There are several teams that helped us get to these latency improvements for inference. We would like to thank the vLLM team for creating the paged attention kernel in a clean and reusable manner. We extend our gratitude to the Team PyTorch at Meta that helped provide feedback on this blog as well as continued efforts on optimal usage of PyTorch. Special thanks to our internal production teams at IBM Research who took this prototype to production and hardened it. A shout out to Stas Bekman for providing insightful comments on the blog resulting in an improved explanation of the tradeoffs between compute, memory, and speculator effectiveness.

The paged attention kernel was integrated into IBM FMS by Josh Rosenkranz and Antoni Viros i Martin. The speculator architecture and training was done by Davis Wertheimer, Pavithra Ranganathan, and Sahil Suneja. The integration of the modeling code with the inference server was done by Thomas Parnell, Nick Hill, and Prashant Gupta.