Introduction

One of the tenets of modern neuroscience is that the brain modifies the

strengths of its synaptic connections (“weights”) during learning in

order to better adapt to its environment. However, the underlying

learning rules (“weight updates”) in the brain are currently unknown.

Many proposals have been suggested, ranging from Hebbian-style

mechanisms that seem biologically plausible but are not very effective

as learning algorithms in that they prescribe purely local changes to

the weights between two neurons that increase only if they activate

together — to backpropagation, which is effective from a learning

perspective by assigning credit to neurons along the entire downstream

path from outputs to inputs, but has numerous biologically implausible

elements.

A major long-term goal of computational neuroscience is to identify

which learning rules actually drive learning in the brain. A further

difficulty is that we do not even have strong ideas for what needs to be

measured in the brain to quantifiably assert that one learning rule is

more consistent with those measurements than another learning rule. So

how might we approach these issues? We take a simulation-based approach,

meaning that experiments are done on artificial neural networks rather

than real brains. We train over a thousand artificial neural networks

across a wide range of possible learning rule types (conceived of as

“optimizers”), system architectures, and tasks, where the ground truth

learning rule is known, and quantify the impact of these choices. Our

work suggests that recording activities from several hundred neurons,

measured semi-regularly during learning, may provide a good basis to

identify learning rules — a testable hypothesis within reach of

current neuroscience tools!

Background: A Plethora of Theories and a Paucity of Evidence

The brain modifies the connections between neurons during learning to

improve behavior; however, the underlying rules that govern these

modifications are unknown. The most famous proposed learning rule is

“Hebbian learning”, also known by the mantra: “neurons that fire

together; wire together”. In this proposal, a synaptic connection

strengthens if one neuron (“pre-synaptic”) consistently sends a signal

to another neuron (“post-synaptic”). The changes prescribed by Hebbian

learning are “local” in that they do not take into account a synapse’s

influence further downstream in the network. This locality makes

learning rather slow even in the cases where additional issues, such as

the weight changes becoming arbitrarily large, are mitigated. Though

there have been many suggested theoretical strategies to deal with this

problem, commonly involving simulations with artificial neural networks

(ANNs), these strategies appear difficult to scale up to solve

large-scale tasks such as ImageNet categorization

[1].

This property of local changes is in stark contrast to backpropagation,

the technique commonly used to optimize artificial neural networks. In

backpropagation, as the name might suggest, an error signal is

propagated backward along the entire downstream path from the outputs of

a model to the inputs of the model. This allows credit to be effectively

assigned to every neuron along the path.

Although backpropagation has long been a standard component of deep

learning, its plausibility as a biological learning rule (i.e. how the

brain modifies the strengths of its synaptic connections) is called into

question for several reasons. Chief among them is that backpropagation

requires perfect symmetry, whereby the backward error-propagating

weights are the transpose of the forward inference weights, for which

there is currently little biological support

[2,

3].

forward and backward weights. This constraint can be relaxed by

uncoupling them, thereby generating a spectrum of learning rule

hypotheses about how the backward weights may be updated.

For more details, see our recent prior work.

Recent approaches, from us and others

[4,

5], introduce approximate

backpropagation strategies that do not require this symmetry, and can

still succeed at large-scale learning as backpropagation does. However,

given the number of proposals, a natural question to ask is how

realistic they are. At the moment, our hypotheses are governed by domain

knowledge that specifies what “can” and “cannot” be biologically

plausible (e.g. “exact weight symmetry is likely not possible” or

“separate forward and backward passes during learning seem

implausible”), as well as characterizations of ANN task performance

under a given learning rule (which is not always directly measurable

from animal behavior). In order to be able to successfully answer this

question, we need to be able to empirically refute hypotheses. In

other words, we would ideally want to know what biological data to

collect in order to claim that one hypothesis is more likely than

another.

More concretely, we can ask: what specific measurements from the brain,

in the form of individual activation patterns over time, synaptic

strengths, or paired-neuron input-output relations, would allow one to

draw quantitative comparisons of whether the observations are more

consistent with one or another specific learning rule? For example,

suppose we record neural responses (“activation patterns”) while an

animal is learning a task. Would these data be sufficient to enable us

to broadly differentiate between learning rule hypotheses, e.g. by

reliably indicating that one learning rule’s changes over time more

closely match the changes measured from real data than those prescribed

by another learning rule?

learning rule hypotheses. (Pyramidal neuron schematic adapted from Figure

4 of [6])

Answering this question turns out to be a substantial challenge, because

it is difficult on purely theoretical grounds to identify which patterns

of neural changes arise from given learning rules, without also knowing

the overall network connectivity and reward target (if any) of the

learning system.

But, there may be a silver lining. While ANNs consist of units that are

highly simplified with respect to biological neurons, recent progress

within the past few years has shown that the internal representations that

emerge in trained deep ANNs often overlap strongly with representations

in the brain, and are in fact quantifiably similar to many

neurophysiological and behavioral observations in animals

[7]. For

instance, task-optimized, deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have

emerged as quantitatively accurate models of encoding in primate visual

cortex [8,

9,

10]. This is

due to (1) their cortically-inspired architecture, a cascade of

spatially-tiled linear and nonlinear operations; and (2) their being

optimized to perform certain behaviors that animals must perform to

survive, such as object recognition

[11]. CNNs trained

to recognize objects on ImageNet predict neural responses of primate

visual cortical neurons better than any other model class. Thus, these

models are, at the moment, some of our current best algorithmic

“theories” of the brain — a system that was ultimately not designed by

us, but rather the product of millions of years of evolution. On the

other hand, ANNs are designed by us — so the ground truth learning

rule is known and every unit (artificial “neuron”) can be measured up to

machine precision.

Can we marry what we can measure in neuroscience with what we can

conclude from machine learning, in order to identify what experimentally

measurable observables may be most useful for inferring the underlying

learning rule? If we can’t do this in our models, then it seems very

unlikely to be able to do this in the real brain. But if we can do this

in principle, then we are in a position to generate predictions as to

what data to collect, and whether that is even within reach of current

experimental neuroscience tools.

Methods

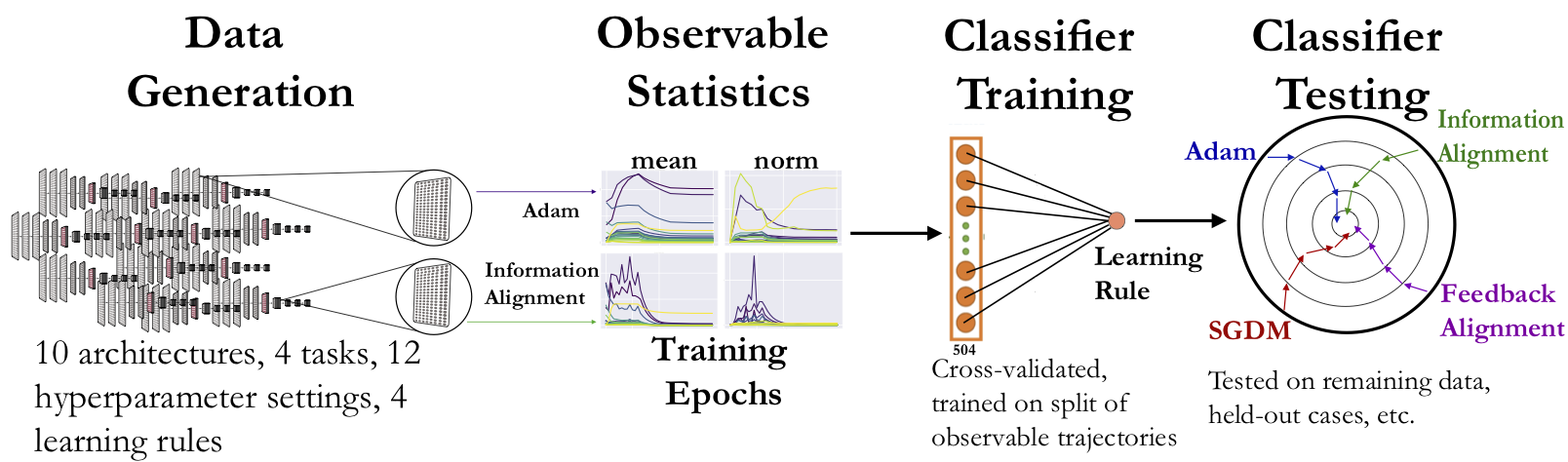

We adopt a two-stage “virtual experimental” approach. In the first

stage, we train ANNs with different learning rules, across a variety of

architectures, tasks, and associated hyperparameters. These will serve

as our “model organisms” on which we will subsequently perform idealized

neuroscience measurements. In the second stage, we calculate aggregated

statistics (“measurements”) from each layer of the models as features

from which to train simple classifiers that classify the category that a

given learning rule belongs to (specified below). These classifiers

include the likes of a linear SVM, as well as simple non-linear ones

such as a Random Forest and a 1D convolutional two-layer perceptron.

neural network’s layer, through the model training process for each

learning rule. We take a quantitative approach whereby a classifier is

cross-validated and trained on a subset of these trajectories and

evaluated on the remaining data.

Generating a large-scale dataset is crucial to this endeavor, in order

to both emulate a variety of experimental neuroscience scenarios and be

able to derive robust conclusions from them. Thus, in the first stage,

we train ANNs on tasks and architectures that have been shown to explain

variance in neural responses from sensory (visual and auditory)

brain areas [8,

12].

These include supervised tasks across vision and audition, as well as

self-supervised ones. We consider both shallow and deep feedforward

architectures on these tasks, that are of depth comparable to what is

considered reasonable from the standpoint of shallower non-primate (e.g.

mouse

[13]) and

deeper primate sensory systems

[8,

14,

15].

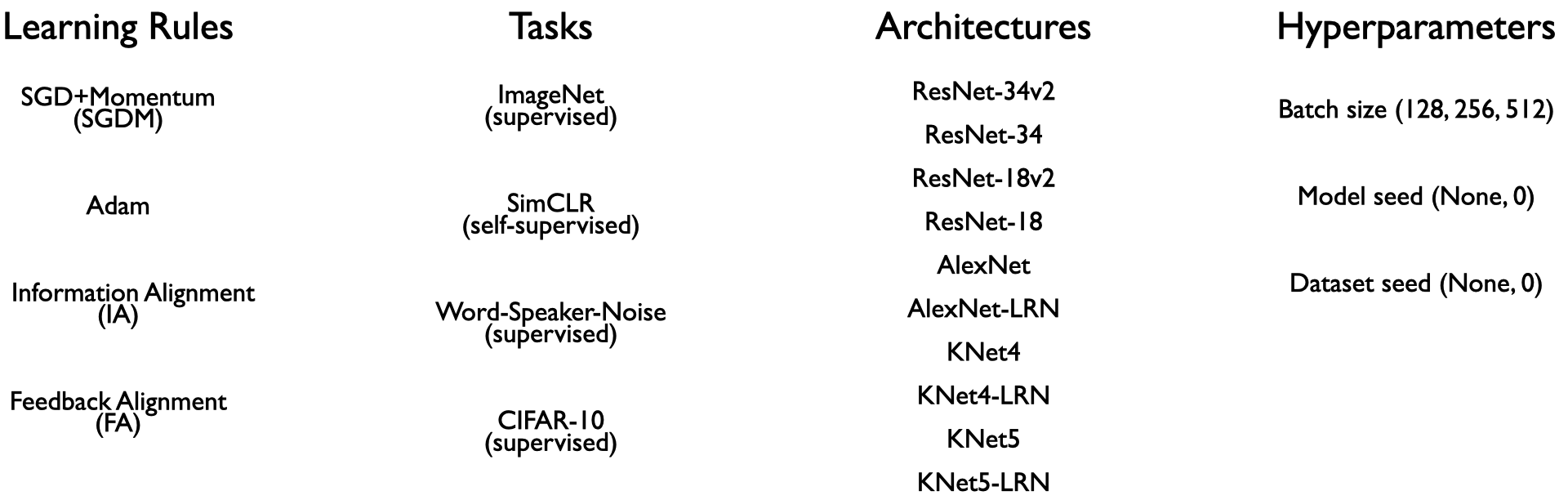

we generate data, comprising over a thousand training experiments in total.

In the second stage, we train classifiers on the observable statistics from these ANNs to predict the learning rules (as specified in the table above) used to train them.

The four learning rules were chosen as they span the space of commonly

used variants of backpropagation (SGDM and Adam), as well as potentially

more biologically-plausible “local” learning rules (Feedback

Alignment (FA) and Information Alignment (IA)) that efficiently

train networks at scale to varying degrees of performance but avoid exact weight

symmetry.

Because the primary aim of this study is to determine the extent that

different learning rules led to different encodings within ANNs, we

begin by defining representative features that can be drawn from the

course of model training. For each layer in a model, we consider three

measurements: weights of the layer, activations from the layer, and

layer-wise activity change of a given layer’s outputs relative to its

inputs. We choose ANN weights to analogize to synaptic strengths in the

brain, activations to analogize to post-synaptic firing rates, and

layer-wise activity changes to analogize to paired measurements that

involve observing the change in post-synaptic activity with respect to

changes induced by pre-synaptic input.

For each measure, we consider three functions applied to it: “identity”,

“absolute value”, and “square”. Finally, for each function of the

weights and activations, we consider seven statistics, and for the

layer-wise activity change observable, we only use the mean statistic

due to computational restrictions. This results in a total of 45

continuous valued observable statistics for each layer, though 24

observable statistics are ultimately used for training the classifiers,

since we remove any statistic that has a divergent value during the

course of model training. We also use a ternary indicator of layer

position in the model hierarchy: “early”, “middle”, or “deep”

(represented as a one-hot categorical variable).

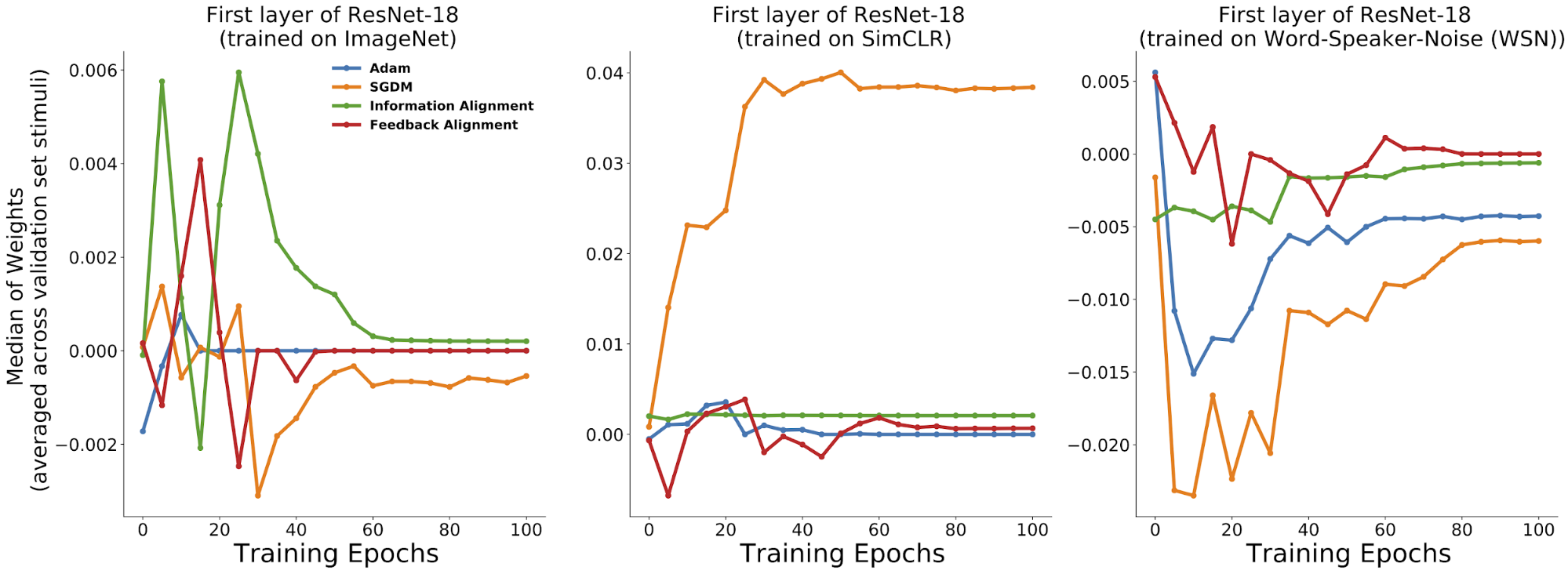

We Can Separate Learning Rules from Aggregate Statistics of the Weights, Activations, or Layer-wise Activity Changes

differences in observable statistics.

Already by eye, one can pick up distinctive differences across the

learning rules for each of the training trajectories of these metrics.

Of course, this is not systematic enough to clearly judge one set of

observables versus another, but provides some initial assurance that

these metrics seem to capture some inherent differences in learning

dynamics across rules.

So these initial observations seem promising, but we want to make this

approach more quantitative. Suppose for each layer we concatenate the

trajectories of each observable and the position in the model hierarchy

that this observable came from. Can we generalize well across held-out

examples?

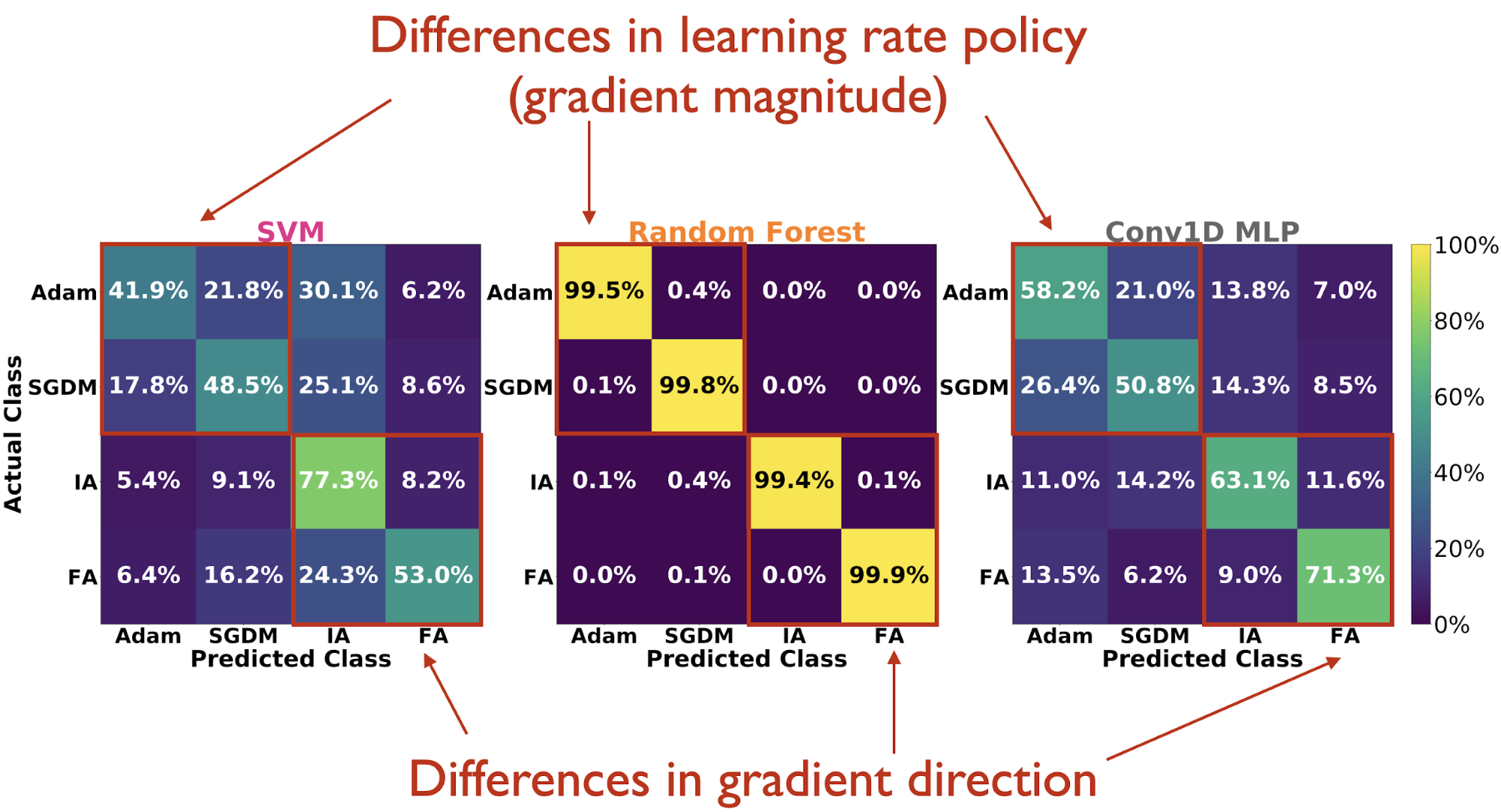

It turns out that the answer is in fact, yes. Across all classes of

observables, the Random Forest attains the highest test accuracy, and

all observable measures perform similarly under this classifier.

(Adam vs. SGDM) are more difficult to distinguish.

Looking at confusion matrices on the test set, we see that the Random

Forest hardly mistakes one learning rule from any of the others. And

when the classifiers do make mistakes, they generally tend to confuse

Adam vs. SGDM more so than IA vs. FA, suggesting that they are able to

pick up more on differences (reflected in the observable statistics) due

to high-dimensional direction of the gradient tensor than the magnitude

of the gradient tensor (the latter being directly tied to learning rate

policy).

Adding Back Some Experimental Neuroscience Realism

Up until this point, we have had access to all input types, the full learning trajectory, and noiseless access to all units when making our virtual measurements of ANN observable statistics.

But in a real experiment where someone were to

collect such data from a neural circuit, the situation would be far from

this ideal scenario. We therefore explore experimental realism in

several ways, in order to identify which observable measures are robust

across these scenarios.

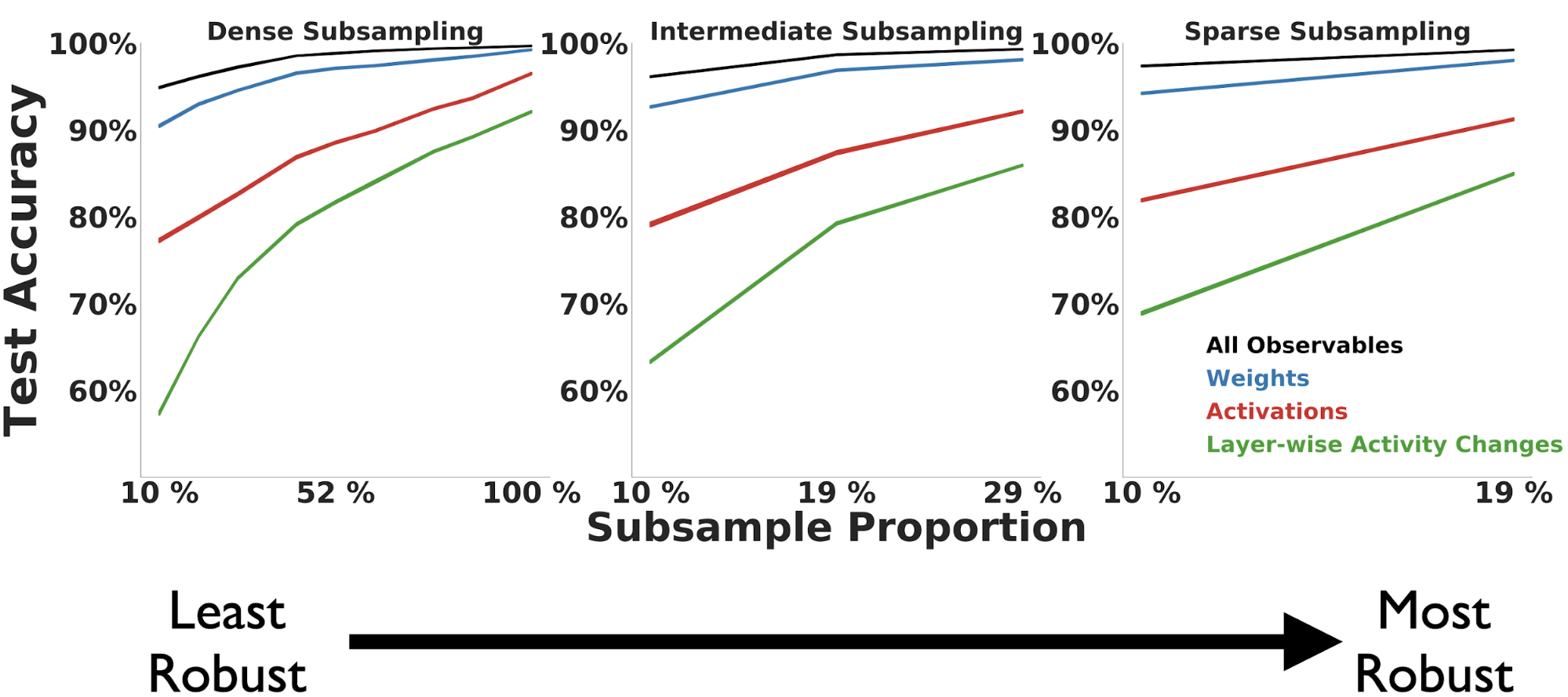

Access to only portions of the learning trajectory: subsampling observable trajectories

The results presented thus far were obtained with access to the entire

learning trajectory of each model. Often however, an experimentalist

collects data throughout learning at regularly spaced intervals. We

capture this variability by randomly sampling a fixed number of points

at a fixed temporal spacing for each trajectory, which we refer to as a

“subsample period”.

trajectory undersampling.

We find across observable measures that robustness to undersampling of

the trajectory is largely dependent on the subsample period length. As

the subsample period length increases (in the middle and right-most

columns), the Random Forest classification performance increases

compared to the same number of sampled points for a smaller period

(depicted in the left-most column).

Taken together, these results suggest that data consisting of

measurements collected temporally further apart across the learning

trajectory is more robust to undersampling than data collected closer

together in training time. Furthermore, across individual observable

measures, the weights are overall the most robust to undersampling of

the trajectory, but with enough frequency of samples we can achieve

comparable performance with the activations.

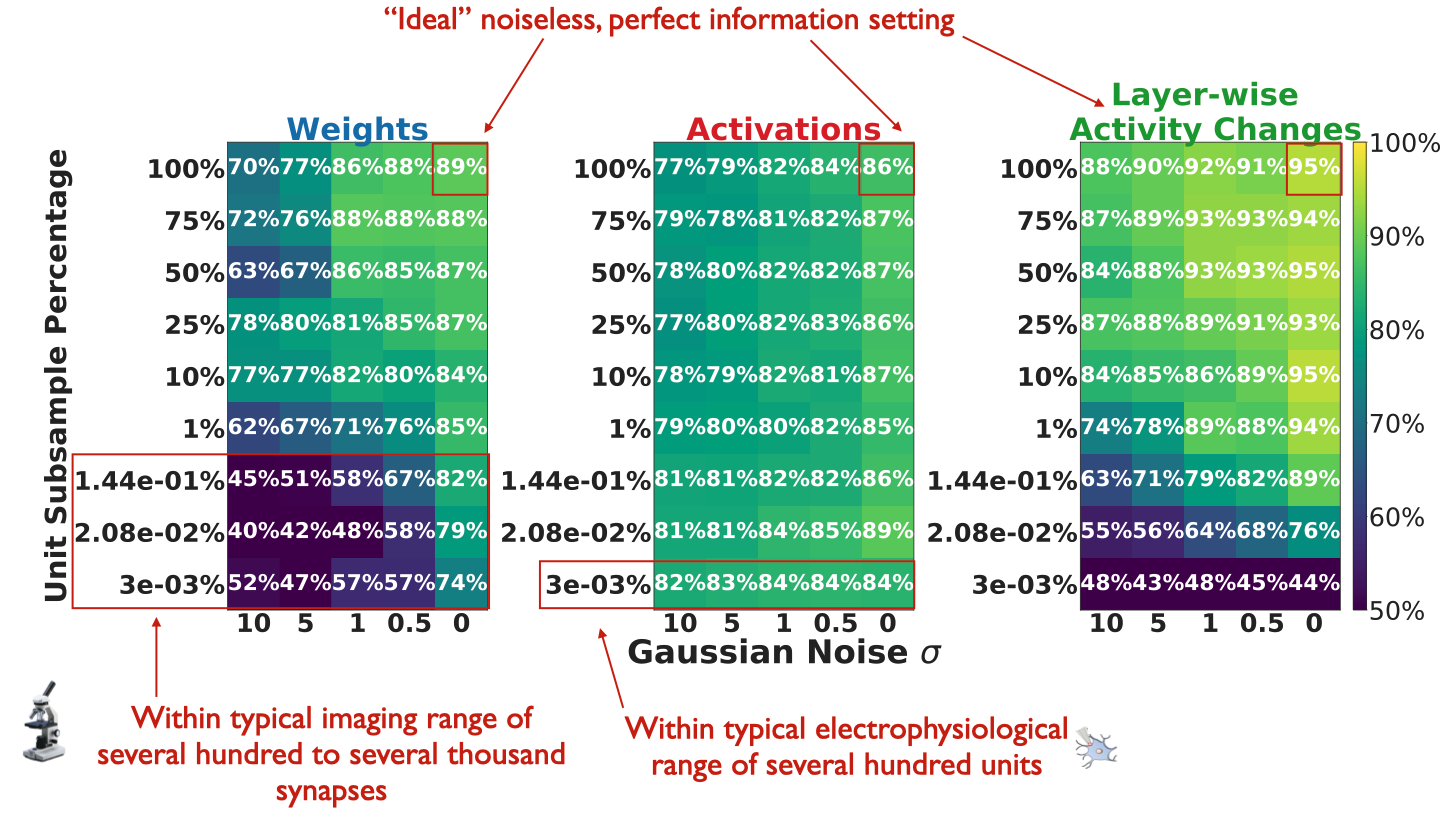

Incomplete and noisy measurements: subsampling units and Gaussian noise before collecting observables

The aggregate statistics computed from the observable measures thus far

have operated under the idealistic assumption of noiseless access to

every unit in the model. However, in most datasets, there is a

significant amount of unit undersampling as well as non-zero measurement

noise. How do these two factors affect learning rule identification, and

in particular, how noise and subsample-robust are particular observable

measures?

Addressing this question would provide insight into the types of

experimental neuroscience paradigms that may be most useful for

identifying learning rules, and predict how certain experimental tools

may fall short for given observables. For instance, optical imaging

techniques can use fluorescent indicators of electrical activities of

neurons to give us simultaneous access to thousands of neurons.

But these techniques can have lower temporal resolution and signal-to-noise than

electrophysiological recordings that more directly measure the

electrical activities of neurons, which in turn may lack the same

coverage.

undersampling. Reported here is Random Forest test set accuracy in

separating IA vs. FA, averaged over 10 train/test splits per random

sampling and simulated measurement noise seed.

To account for these tradeoffs, we model measurement noise as an

additive white Gaussian noise process added to units of ResNet-18

trained on the ImageNet and self-supervised SimCLR tasks. We choose IA

vs. FA since the differences between them are conceptually stark: IA

imposes dynamics on the feedback error weights during learning, whereas

FA keeps them fixed. If there are scenarios of measurement noise and

unit subsampling where we are at chance accuracy for this problem (50%),

then it may establish a strong constraint on learning rule

separability more generally.

Our results suggest that if one makes experimental measurements by

imaging synaptic strengths, it is still crucial that the optical imaging

readout not be very noisy, since even with the amount of units typically

recorded currently (on the order of several hundred to several thousand

synapses), a noisy imaging strategy of synaptic strengths may be

rendered ineffective.

Instead, current electrophysiological techniques that measure the

activities from hundreds of units could form a good set of neural data

to separate learning rules. Recording more units with these techniques

can improve learning rule separability from the activities, but it does

not seem necessary, at least in this setting, to record a majority of

units to perform this separation effectively.

Conclusions

As experimental techniques in neuroscience continue to advance, we will

be able to record data from more neurons with higher temporal

resolution. But even if we had the perfect measurement tools, it is not

clear ahead of time what should be measured in order to identify the

learning rule(s) operative within a given neural circuit, or whether

this is even possible in principle. Our model-based approach

demonstrates that we can identify learning rules solely on the basis of

standard types of experimental neuroscience measurements from the

weights, activations, or layer-wise activity changes, without knowledge

of the architecture or loss target of the learning system.

Additionally, our results suggest the following prescription for the type of

experimental neuroscience data to be collected towards this goal:

Electrophysiological recordings of post-synaptic activities

from a neural circuit on the order of several hundred units, frequently

measured at wider intervals during the course of learning, may provide a

good basis on which to identify learning rules.

We have made our dataset, code, and interactive

tutorial publicly

available so that others can analyze these properties without needing to

train neural networks themselves. Our dataset may also be of interest to

researchers theoretically or empirically investigating learning in deep

neural networks. For further details, check out our NeurIPS 2020

paper.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my collaborator Sanjana Srivastava

and advisors Surya Ganguli and Daniel Yamins. I would also like to

thank Jacob Schreiber, Sidd Karamcheti, and Andrey Kurenkov for their

editorial suggestions on this post.