[Summary] tl;dr:

A tremendous amount of effort has been poured into training AI algorithms to competitively play games that computers have traditionally had trouble with, such as the retro games published by Atari, Go, DotA, and StarCraft II. The practical machine learning knowledge accumulated in developing these algorithms has paved the way for people to now routinely train game-playing AI agents for many games. Following this line of work, we focus on a specific category of games – those developed by students as part of a programming assignment. Can the same algorithms that master Atari games help us grade these game assignments? In our recent NeurIPS 2021 paper, we illustrate the challenges in treating interactive coding assignment grading as game playing and introduce the Play to Grade Challenge.

Introduction

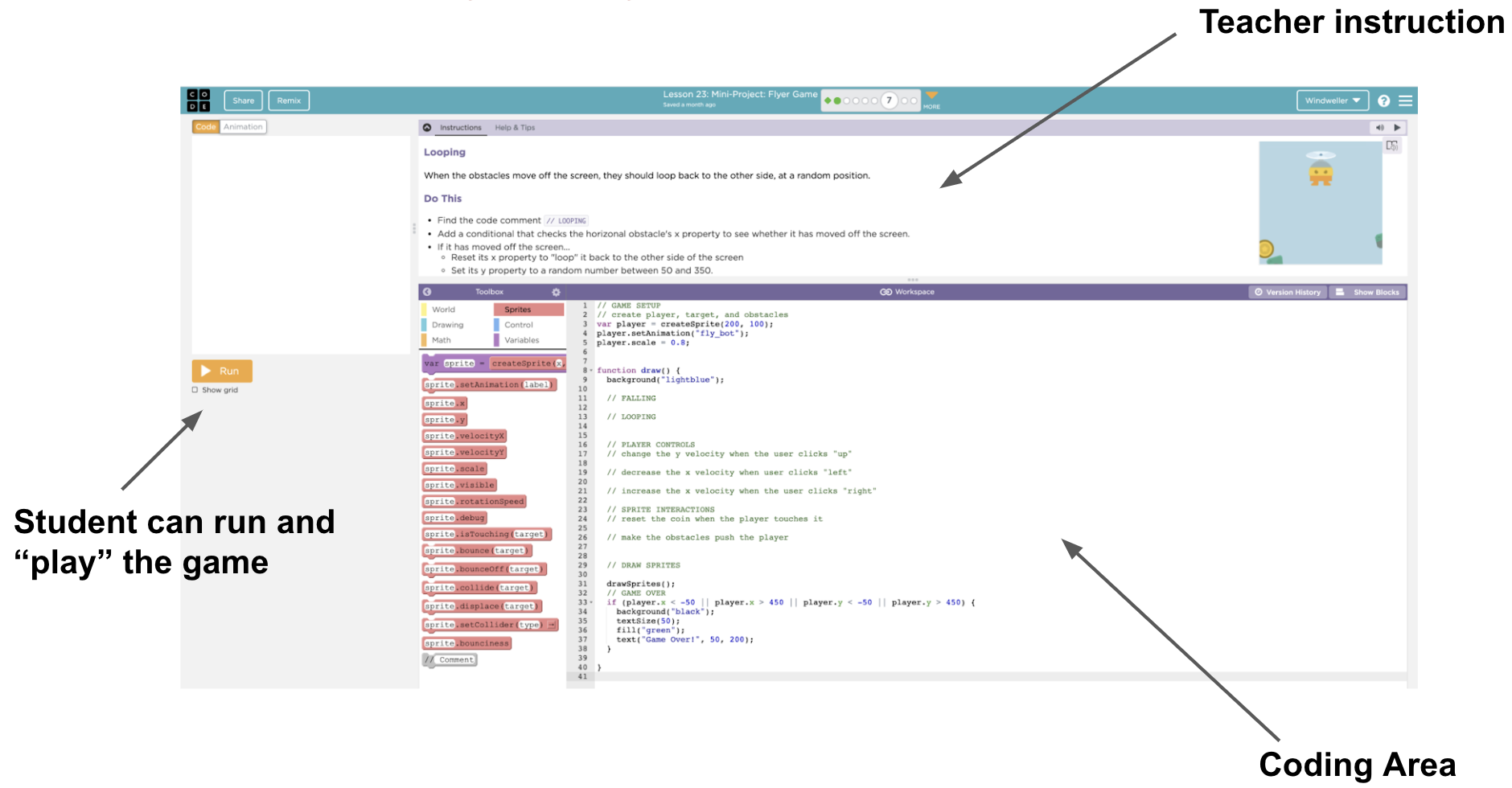

Massive Online Coding Education has reached striking success over the past decade. Fast internet speed, improved UI design, code editors that are embedded in a browser window allow educational platforms such as Code.org to build a diverse set of courses tailored towards students of different coding experiences and interest levels (for example, Code.org offers “Star War-themed coding challenge,” and “Elsa/Frozen themed for-loop writing”). As a non-profit organization, Code.org claims to have reached over 60 million learners across the world 1. Such organizations typically provide a variety of carefully constructed teaching materials such as videos and programming challenges.

A challenge faced by these platforms is that of grading assignments. It is well known that grading is critical to student learning 2, in part because it motivates students to complete their assignments. Sometimes manual grading can be feasible in small settings, or automated grading used in simple settings such as when assignments are multiple choice or adopt a fill-in-the-blink modular coding structure. Unfortunately, many of the most exciting assignments, such as developing games or interactive apps, are also much more difficult to automatically evaluate. For such assignments, human teachers are currently needed to provide feedback and grading. This requirement, and the corresponding difficulty with scaling up manual grading, is one of the biggest obstacles of online coding education. Without automated grading systems, students who lack additional teacher resources cannot get useful feedback to help them learn and advance through the materials provided.

Programming a game that is playable is exciting for students who are learning to code. Code.org provides many game development assignments in their curriculum. In these assignments, students write JavaScript programs in a code editor embedded in the web browser. Game assignments are great for teachers to examine student’s progress as well: students not only need to grasp basic concepts like if-conditionals and for-loops but use these concepts to write the physical rules of the game world — calculate the trajectories of objects, resolve inelastic collision of two objects, and keep track of game states. To deal with all of these complexities, students need to use abstraction (functions/class) to encapsulate each functionality in order to manage this complex set of logic.

Automated grading on the code text alone can be an incredibly hard challenge, even for introductory level computer science assignments. As examples, two solutions which are only slightly different in text can have very different behaviors, and two solutions that are written in very different ways can have the same behaviors. As such, some models that people develop for grading code can be as complex as those used to understand paragraphs of natural language. But, sometimes, grading code can be even more difficult than grading an essay because coding submissions can be in different programming languages. In this situation, one must not only develop a program that can understand many programming languages, but guard against the potential that the grader is more accurate for some languages than others. A Finally, these programs must be able to generalize to new assignments because correct grading is just as necessary for the first student working on an assignment as the millionth – the collect-data, train, deploy cycle is not quite suitable in this context. We don’t have the luxury of collecting a massive amount of labeled dataset to train a fully supervised learning algorithm for each and every assignment.

In a recent paper, we circumvent these challenges by developing a method that grades assignments by playing them, without needing to look at the source code at all. Despite this different approach, our method still manages to provide scalable feedback that potentially can be deployed in a massively-online setting.

The Play to Grade Challenge

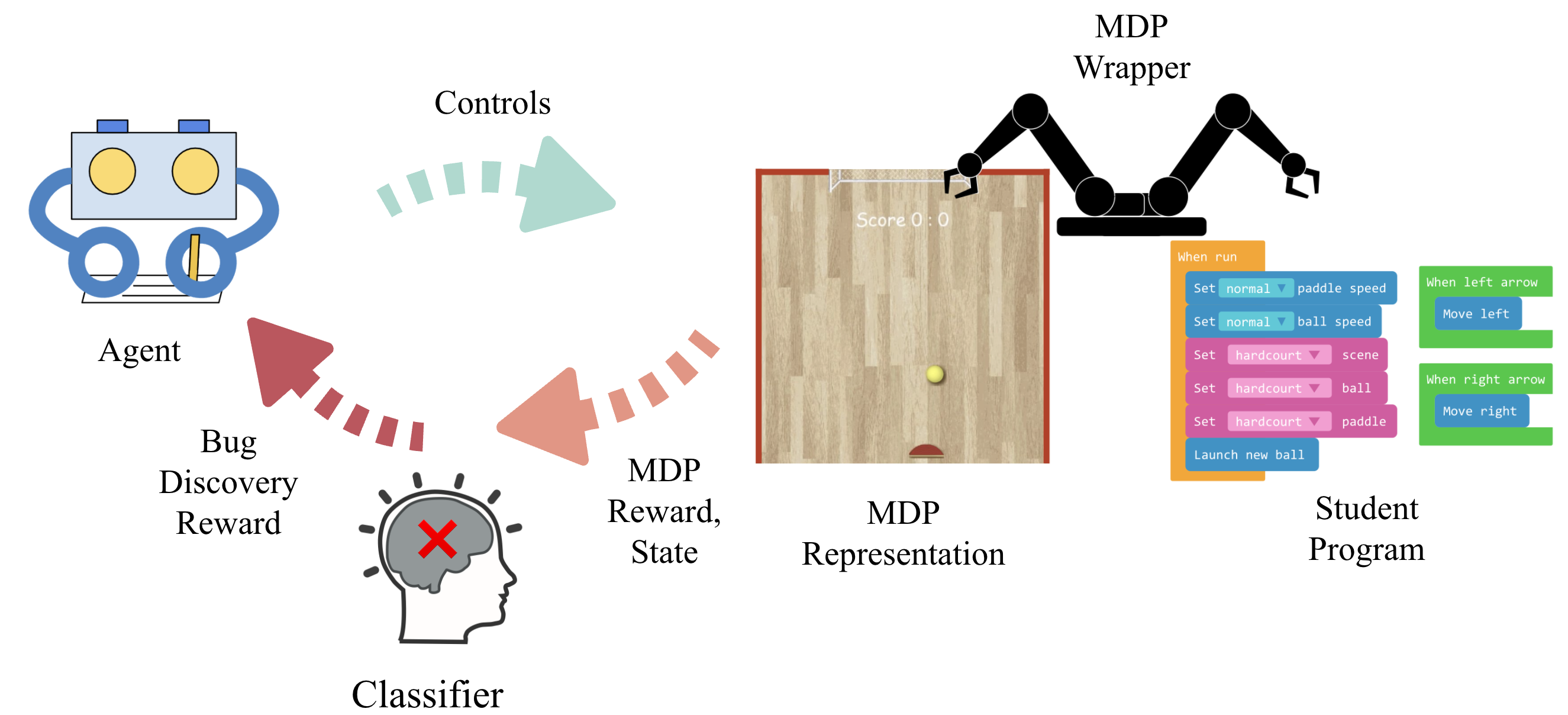

Our solution to these problems is to ignore the code text entirely and to grade an assignment by having a grading algorithm play it. We represent the underlying game of each program submission as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), which defines a state space, action space, reward function, and transition dynamics. By running each student’s program, we can build the MDP directly without needing to read or understand the underlying code. You can read more about the MDP framework here: 3.

Since all student programs are written for the same assignment, these programs should generate MDP with a lot of commonalities, such as shared state and action space. After playing the game and fully constructing the MDP for an assignment, all we need is to compare the MDP specified by the student’s program (student MDP) to the teacher’s solution (reference MDP) and determine if these two MDPs are the same. What sets this challenge apart from any other reinforcement learning problems is the fact that a classification needs to be made at the end of this agent’s interaction with this MDP — the decision of whether the MDP is the same as the reference MDP or not.

In order to solve this challenge, we present an algorithm with two components: an agent that plays the game and can reliably reach bug states, and a classifier that can recognize bug states (i.e., provide the probability of the observed state being a bug). Both components are necessary for accurate grading: an agent that reaches all states but cannot determine if any represents bugs is just as bad as a perfect classifier paired with an agent that is bad at taking actions which might cause bugs. Imagine a non-optimal agent that never catches the ball (in the example above) – this agent will never be able to test if the wall, or paddle, or goal does not behave correctly.

An ideal agent needs to produce differential trajectories, i.e., sequences of actions that can be used to differentiate two MDPs, and must contain at least one bug-triggering state if the trajectory is produced from the incorrect MDP. Therefore, we need both a correct MDP and a few incorrect MDPs to teach the agent and the classifier. These incorrect MDPs are incorrect solutions that can either be provided by the teacher, or come from manually grading a few student programs to find common issues. Although having to manually label incorrect MDPs is an annoyance, we show that the total amount of effort is generally significantly lower than grading each assignment: in fact, we show that for the task we solve in the paper, you only need 5 incorrect MDPs to reach a decent performance (see the appendix section of our paper).

Recognizing Bugs from Scratch

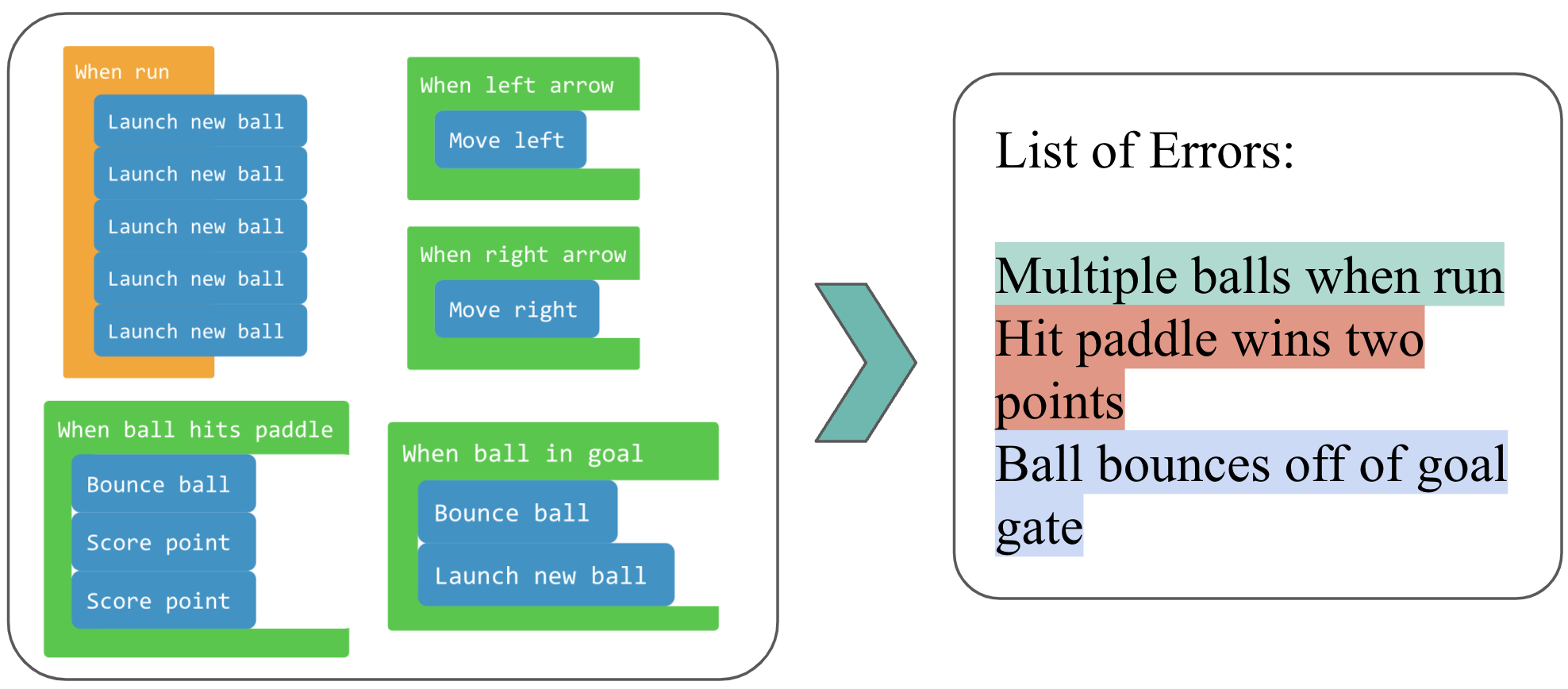

Here are three incorrect programs and what they look like when played. Each incorrect program behaves differently from the correct program:

- One program’s wall does not allow the ball to bounce on it.

- Another program’s goal post does not let the ball go through.

- The last program spawns 2 new balls whenever the ball bounces on the wall.

A challenge with building differential trajectories is that one must know which state is a bug triggering state. Previous works 456 have made the strong assumption that one would automatically know when they encountered a bug, potentially because they expect the game program to crash after encountering a bug. Because of this assumption, they focus their efforts on building pure-exploration agents that try to visit as many states as possible. However, in reality, bugs can be difficult to identify and do not all cause the game to crash. For example, a ball that is supposed to bounce off of a wall is now piercing through it and flying off into oblivion. These types of behavioral anomalies motivate the use of a predictive model that can take in the current game state and determine whether it is anomalous or not.

Unfortunately, training a model to predict if a state is a bug state is non-trivial. This is because, although we have labels for some MDPs, these labels are not on the state-level (i.e., not all states in an incorrect MDP are bug states). Put another way, our labels can tell us when a bug has been encountered but cannot tell us what specific action caused the bug. The determination of whether bugs exist in a program can be framed as a chicken-and-egg problem where, if bug states could be unambiguously determined one would only need to explore the state space, and if the exploration was optimal one would only need to figure out how to determine if the current state exhibited a bug.

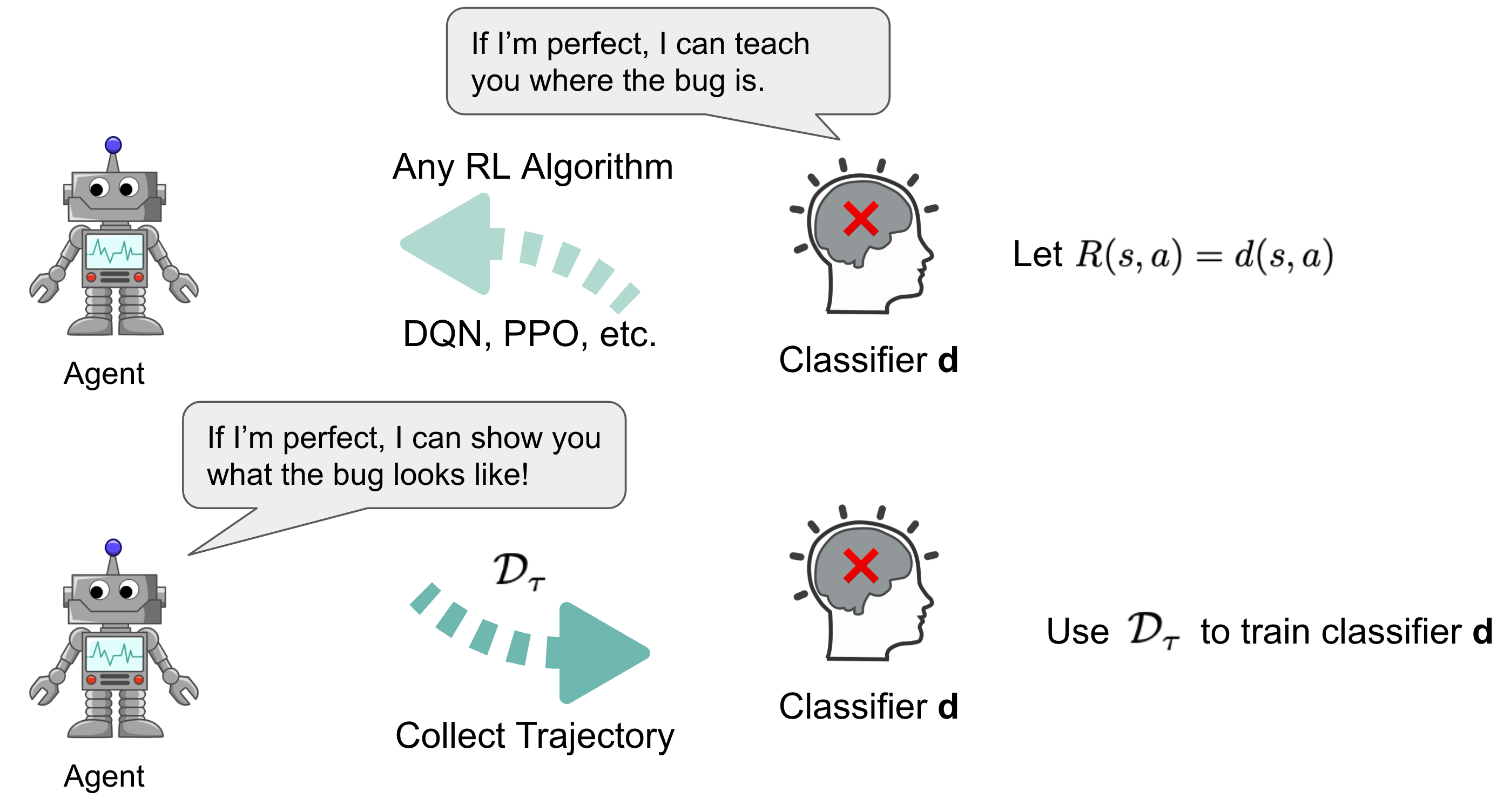

Collaborative Reinforcement Learning

Fortunately, these types of problems can generally be solved through the expectation-maximization framework, which involves an intimate collaboration between the neural network classifier and the reinforcement learning agent. We propose collaborative reinforcement learning, an expectation-maximization approach, where we use a random agent to produce a dataset of trajectories from the correct and incorrect MDP to teach the classifier. Then the classifier would assign a score to each state indicating how much the classifier believes the state is a bug-triggering state. We use this score as reward and train the agent to reach these states as often as possible for a new dataset of trajectories to train the classifier.

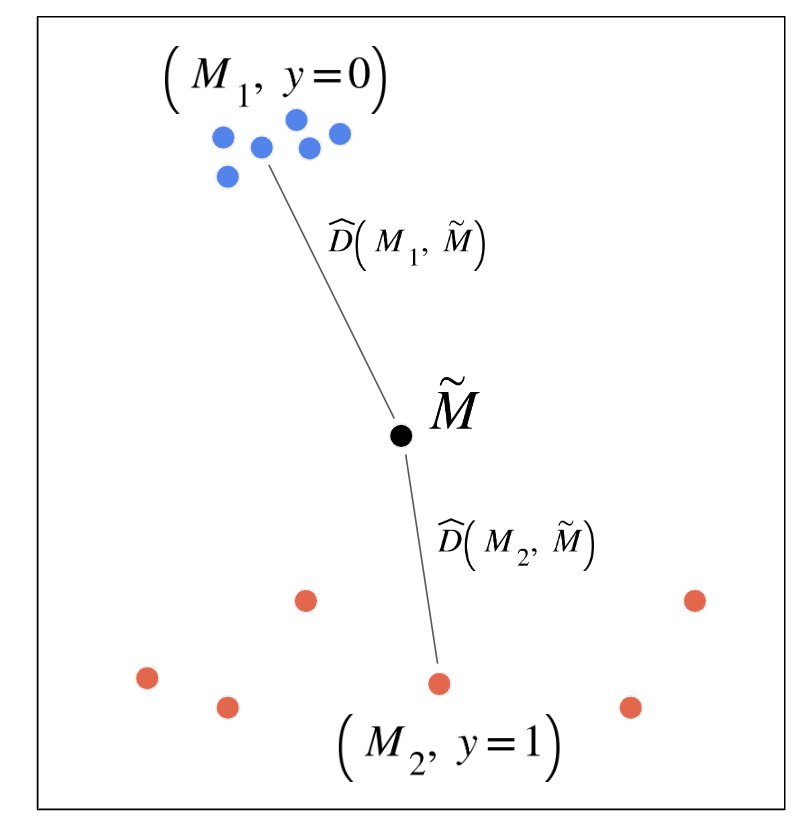

After using the RL agent to interact with the MDP to produce trajectories, we can try out different ways to learn a classifier that can classify a state as a bug or not (a binary label). Choosing the right label is important because this label will become the reward function for the agent, so it can learn to reach bug states more efficiently. However, we only know if the MDP (the submitted code) is correct or broken, but we don’t have labels for the underlying states. Learning state-level labels becomes a challenge!

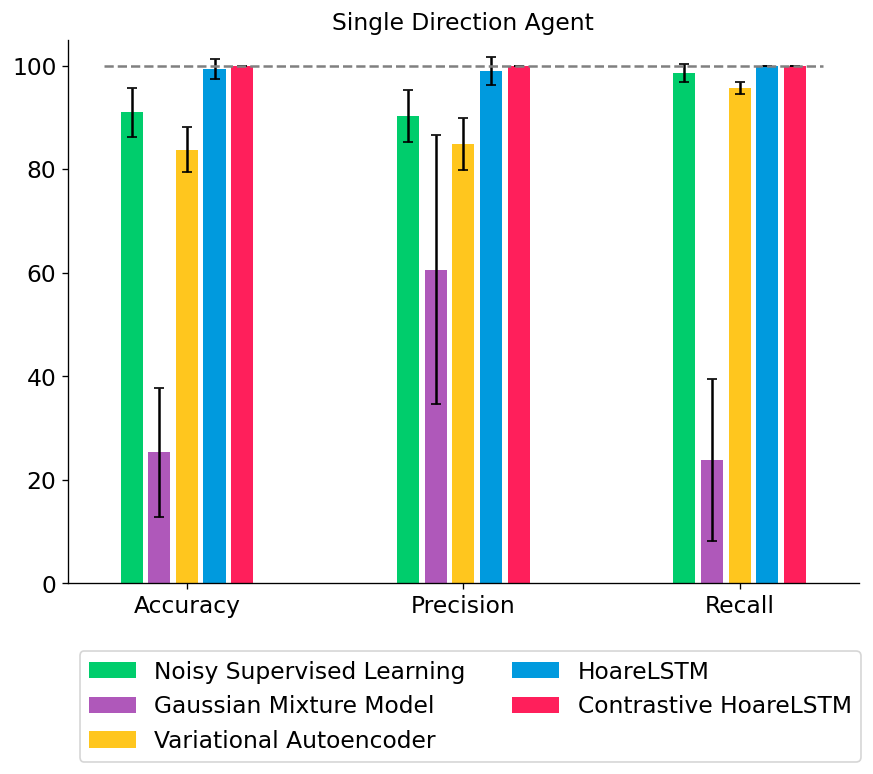

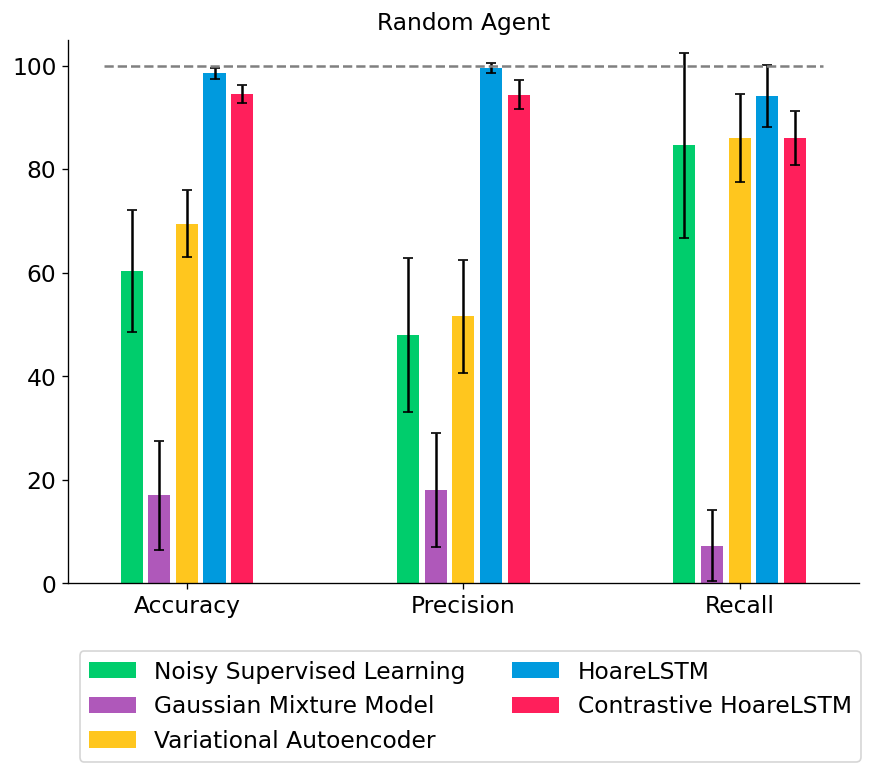

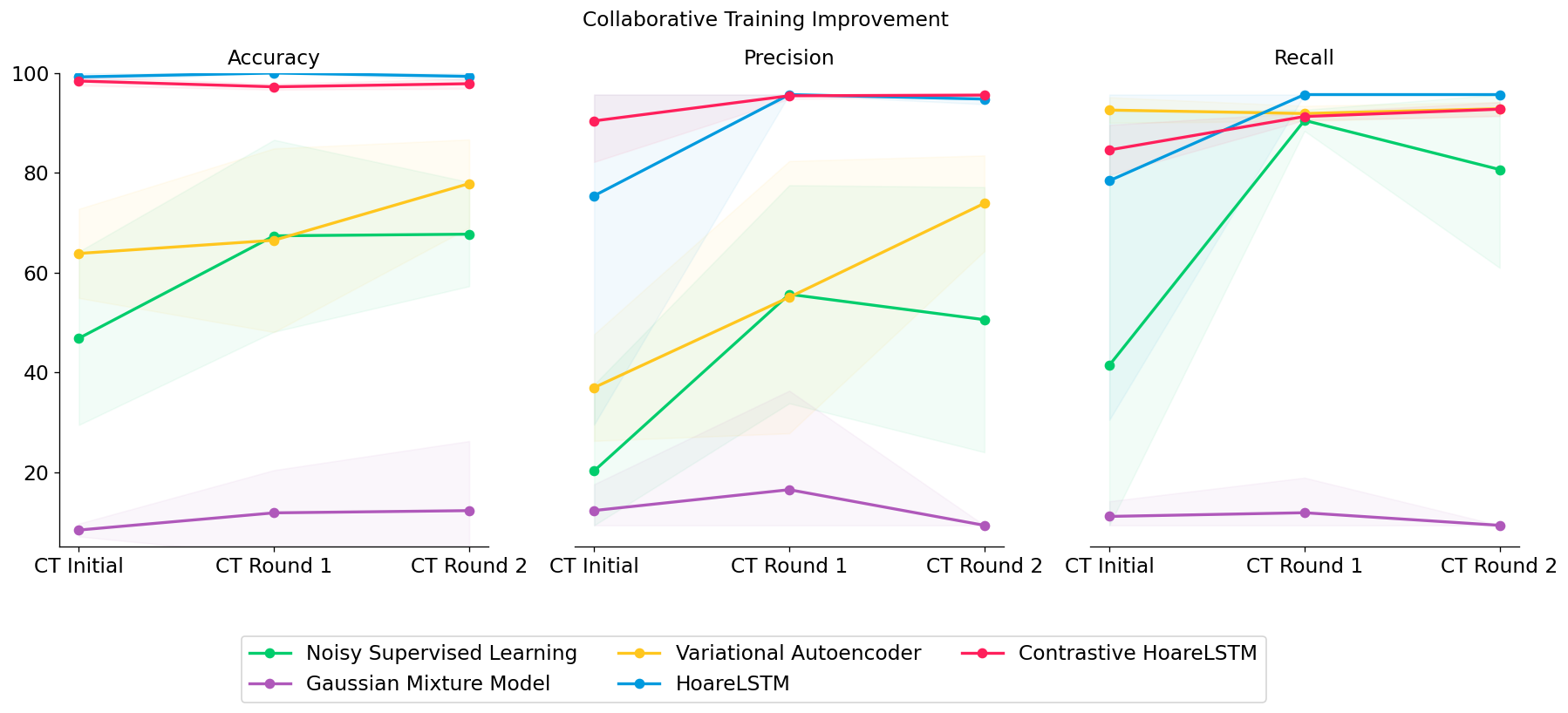

We tested out several types of classifiers: (1) a noisy classifier that classifies all states in a broken MDP as broken, (2) a Gaussian Mixture Model that treats all states independently, (3) a Variational Autoencoder that also treats all states independently but directly models non-linear interactions among the features, or (4) an LSTM that jointly models the teacher program as an MDP (HoareLSTM) and an LSTM that models the student program as an MDP (Contrastive HoareLSTM) – with a distance function that compares the two MDPs, borrowing distance notions from literature in MDP homomorphism78910.

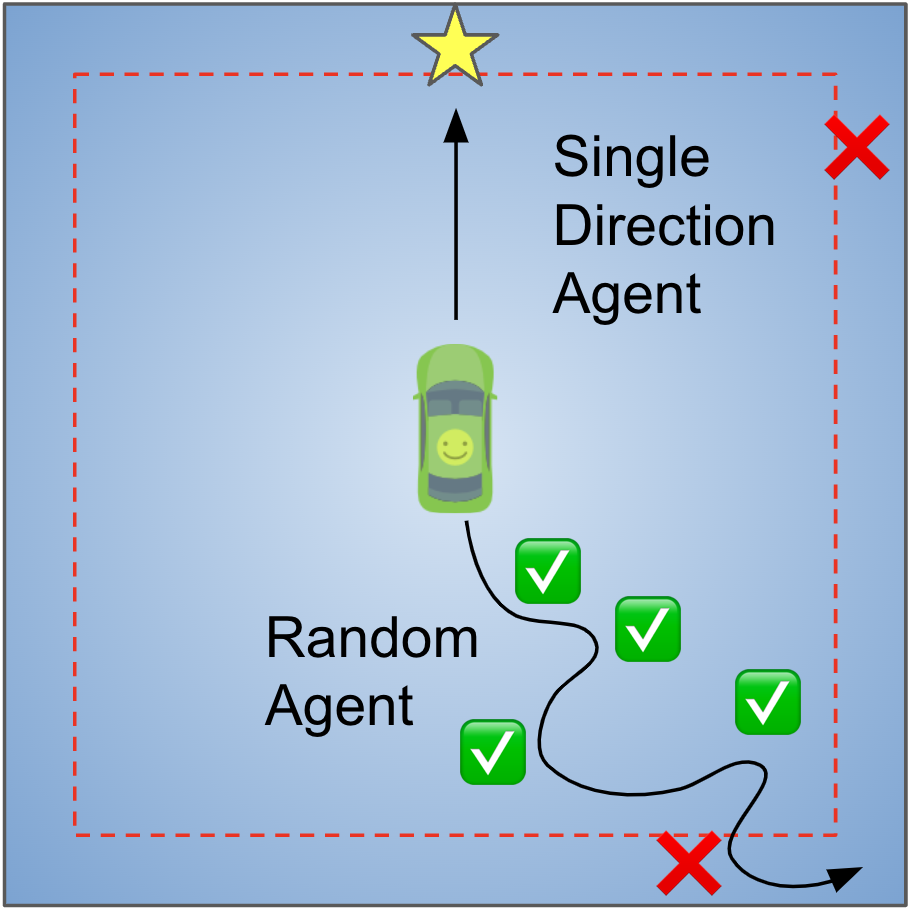

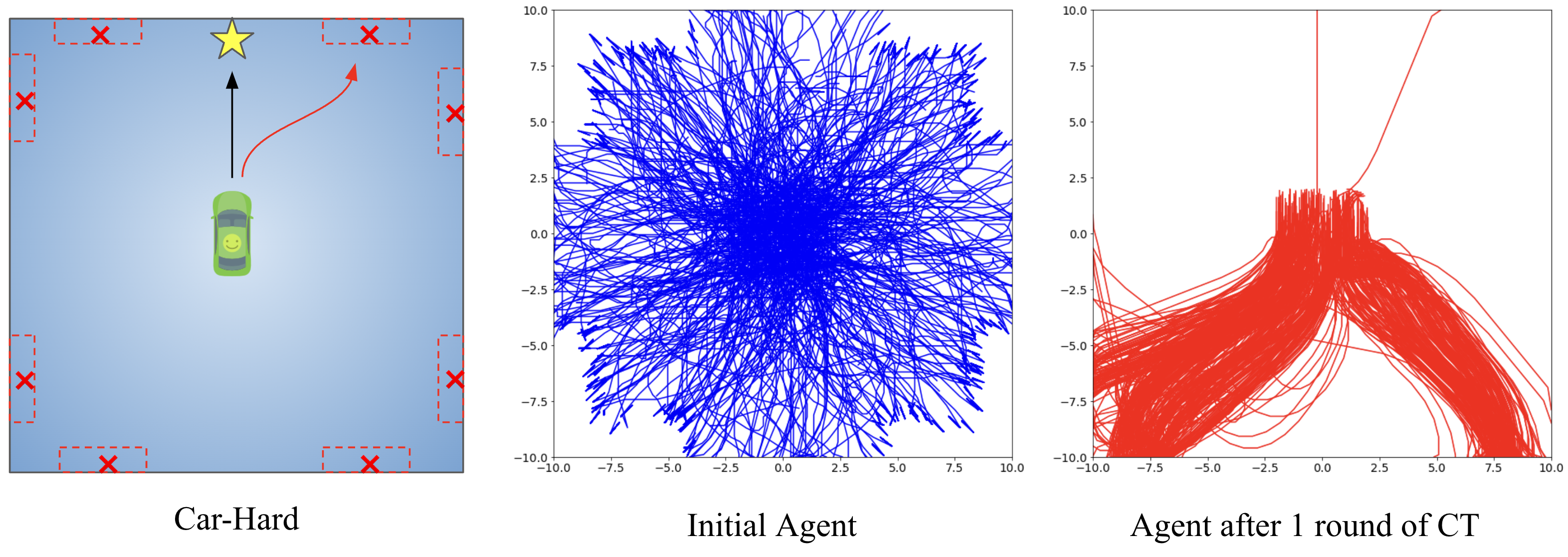

In this toy environment, the agent drives a car on a 2D plane. Whenever the agent drives the car into the outer rim of this area (space between the boundary and red dotted line), a bug will cause the car to get stuck (Leftmost panel in Figure 5). Being stuck means the car’s physical movement is altered, resulting in back-and-forth movement around the same location. The bug classifier needs to recognize the resulting states (position and velocity) of the car being “stuck”, by correctly outputting a binary label (bug) for these states.

In this setting, there is only one type of bug. Most classifiers do well when the agent only drives a straight line (single-direction agent). However, when the agent randomly samples actions at each state, simpler classifiers can no longer differentiate between bug and non-bug states with high accuracy.

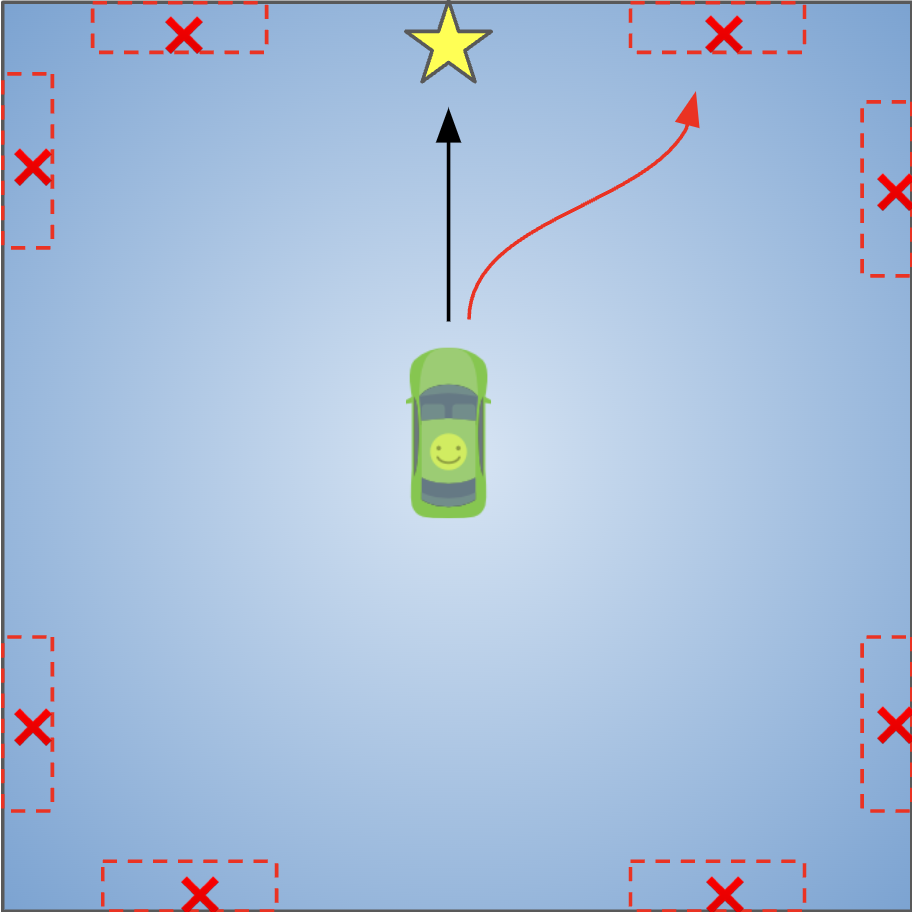

We can increase the difficulty of this setting to see if collaborative training can make the agent operate in the environment with an intention to trigger bugs. In this toy environment, now the bugs will only be triggered in red boxes (Leftmost panel in Figure 6 below). We can see that with only one round of collaborative training (“CT Round 1”), the performances of ALL classifiers are improved, including weaker classifiers. This is understandable, as the agent learns to gradually collect better datasets to train classifiers – and higher quality datasets lead to stronger classifiers. For example, variational auto-encoder started only with 32% precision, but it increased to 74.8% precision after 2 rounds of collaborative training.

We can also visualize how the collaborative training quickly allows the agent to learn to explore states that most-likely contain bugs by visualizing the trajectories (see figure below). Initially the agent just explores the space uniformly (blue curves), but after one round of collaborative training (CT), it learns to focus on visiting the potential bug areas (regions marked by red boxes) (red curves).

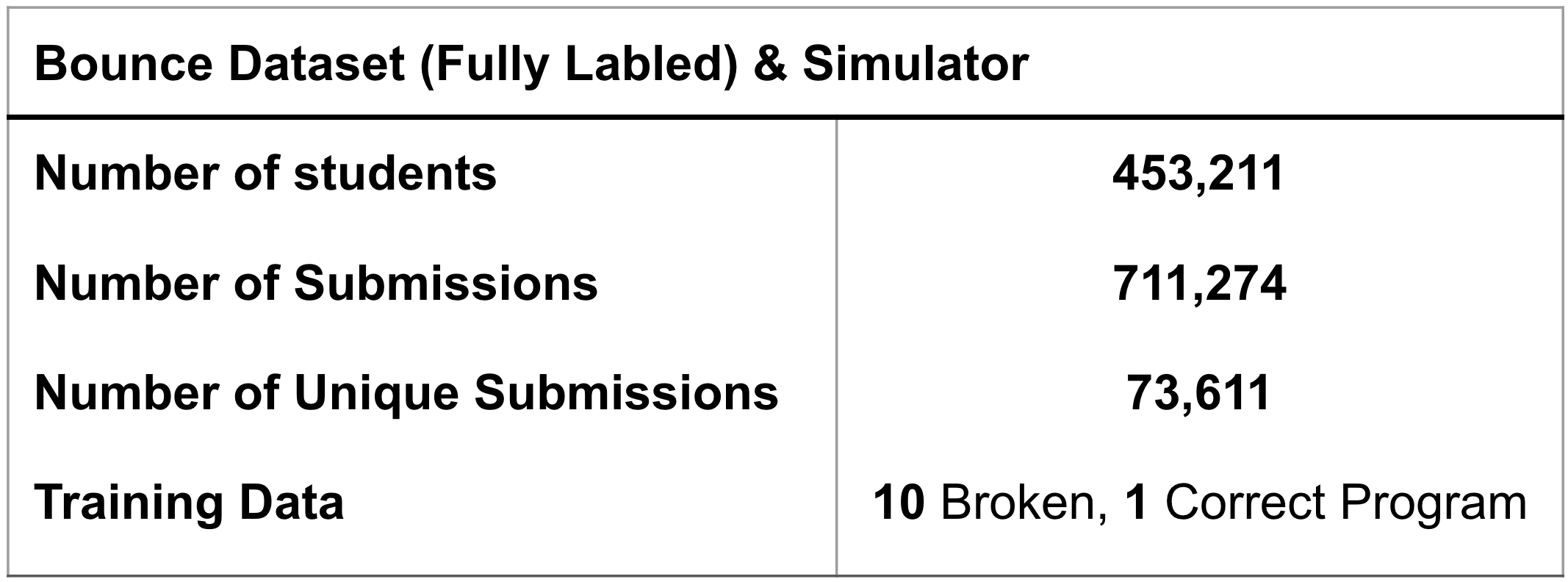

Grading Bounce

Next, we returned to the motivating example for this type of approach: grading real student submissions. With help from Code.org, we are able to verify the algorithm’s performance on a massive amount of unlabeled, ungraded student submissions. The game Bounce, from Code.org’s Course3 for students in 4th and 5th grade, provides a real-life dataset of what variations of different bugs and behaviors in student programs should look like. The dataset is compiled of 453,211 students who made an attempt on this assignment. In total, this dataset consists of 711,274 programs.

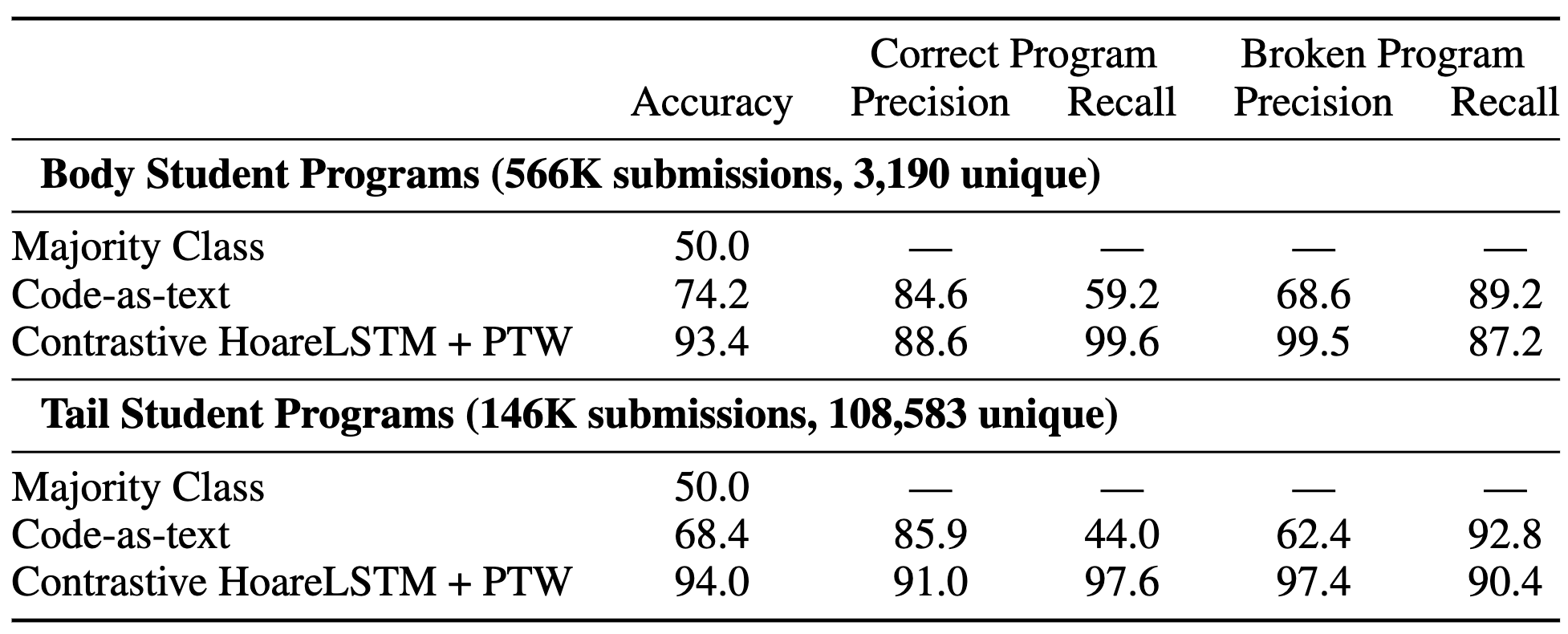

We train our agent and classifier on 10 broken programs that we wrote without looking at any of the student’s submissions. The 10 programs contain bugs that we “guess” to be most likely to occur, and we use them to train 10 agents that learn to reach bug states in these 10 programs. This means that in our training dataset, we have 1 correct program and 10 broken programs. Even with only 11 labeled programs, our agent and classifier can get 99.5% precision at identifying a bug program and 93.4-94% accuracy overall – the agent is able to trigger most of the bugs and the classifier recognizes the bug states using only 10 broken programs. Though for other games, especially more complicated games, the number of training programs will vary. We strongly believe the number is still in magnitude smaller than training supervised code-as-text algorithms. This demonstration shows the promise of reformulating code assignment grading as the Play to Grade.

What is Next?

We started this project by making the argument that sometimes it is far easier to grade a complex coding assignment not by looking at the code text but by playing it. Using Bounce, we demonstrated that in the simple task of identifying if a program has a bug or not (a binary task, nonetheless), we are able to achieve striking accuracy with only 11 labeled programs. We provide a simulator and all of the student’s programs on this Github repo.

Multi-label Bounce

One promising direction for future work is to expand beyond pass/fail binary feedback, and actually identify which bug is in the student’s program and provide that information. Our Bounce dataset enables this by providing multi-error labels, as shown in the table below. The multi-error label setting was not solved by our current algorithm and remains an open challenge!

More than One Correct Solution

Oftentimes, students create solutions that are creative. Creative solutions are different, but not wrong. For example, students can change the texture pattern of the ball or paddle; or they can make the paddle move much faster. How to set the boundary between “being creative” and “being wrong”? This is not a discussion that happens often in AI, but is of huge importance in education. Though we didn’t use the Bounce dataset to focus on the problem of understanding creativity, our work can still use distance measures to set a “tolerance threshold” to account for creativity.

For Educators

We are interested in collecting a suite of interactive coding assignments and creating a dataset for future researchers to work on this problem. Feel free to reach out to us and let us know what you would consider as important in grading and giving students feedback on their coding assignments!

Conclusion

Providing automated feedback for coding is an important area of research in computational education, and an important area for building fully autonomous coding education pipeline (that can generate coding assignment, grade assignment, and teach interactively). Providing a generalizable algorithm that can play interactive student programs in order to give feedback is an important problem for education and an exciting intellectual challenge for the reinforcement learning community. In this work, we introduce the challenge and a dataset, set up the MDP distance framework that is highly data efficient, algorithms that achieve high accuracy, and demonstrate this is a promising direction of applying machine learning to assist education.

This blog post is based on the following paper:

- “Play to Grade: Testing Coding Games as Classifying Markov Decision Process.” Allen Nie, Emma Brunskill, and Chris Piech. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (2021). Link

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Emma Brunskill, Chris Piech for their guidance on the project. Many thanks to Mike Wu, Ali Malik, Yunsung Kim, Lisa Yan, Tong Mu, and Henry Zhu for their discussion and feedback. Special thanks to code.org, and Baker Franke, for many years of collaboration and generously providing the research community with data. Thanks to Stanford Hoffman-Yee Human Centered AI grant for supporting AI in education. Thanks for the numerous rounds of edits from Megha Srivastava and Jacob Schreiber.

-

Code.org displays this statistics on their landing webpage. ↩

-

William G Bowen. The ‘cost disease’ in higher education: is technology the answer? The Tanner Lectures Stanford University, 2012. ↩

-

https://lilianweng.github.io/lil-log/2018/02/19/a-long-peek-into-reinforcement-learning.html ↩

-

Gordillo, Camilo, Joakim Bergdahl, Konrad Tollmar, and Linus Gisslén. “Improving Playtesting Coverage via Curiosity Driven Reinforcement Learning Agents.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.13798 (2021). ↩

-

Zhan, Zeping, Batu Aytemiz, and Adam M. Smith. “Taking the scenic route: Automatic exploration for videogames.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.03125 (2018). ↩

-

Zheng, Yan, Xiaofei Xie, Ting Su, Lei Ma, Jianye Hao, Zhaopeng Meng, Yang Liu, Ruimin Shen, Yingfeng Chen, and Changjie Fan. “Wuji: Automatic online combat game testing using evolutionary deep reinforcement learning.” In 2019 34th IEEE/ACM International Conference on Automated Software Engineering (ASE), pp. 772-784. IEEE, 2019. ↩

-

Pablo Samuel Castro, Prakash Panangaden, and Doina Precup. Equivalence relations in fully and partially observable markov decision processes. In Twenty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2009. ↩

-

Lihong Li, Thomas J Walsh, and Michael L Littman. Towards a unified theory of state abstraction for mdps. ISAIM, 4:5, 2006. ↩

-

Elise van der Pol, Thomas Kipf, Frans A Oliehoek, and Max Welling. Plannable approximations to mdp homomorphisms: Equivariance under actions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.11963, 2020. ↩

-

Robert Givan, Thomas Dean, and Matthew Greig. Equivalence notions and model minimization in markov decision processes. Artificial Intelligence, 147(1-2):163–223, 2003. ↩